[ad_1]

The risk of prolonged stagflation in Britain increased after consumer prices surged more than expected and economic growth slowed to a crawl.

Recent official and informal economic data fell short of analysts’ expectations, prompting many to warn of stagflation and even economic contraction in the second quarter of the year.

Some experts say the government is not doing enough to help families with their problems. cost of living crisis due to soaring consumer price inflation. Opposition parties in parliament have also accused Chancellor Rishi Sunak of insufficient support for Britons dealing with rising energy and food bills.

Stagflation, which refers to slow gross domestic product growth combined with high inflation, is a relatively rare economic condition that can put enormous pressure on consumers and businesses.

Last week, official data showed that consumer price rise The annual growth rate in March was 7%, the fastest pace since 1992. In contrast, GDP slowing down Real wages, adjusted for inflation, contracted by 1% in February, at just 0.1%.

Paul Hollingsworth, an economist at consultancy BNP Paribas Markets 360, said the figures “underscore the risk of a stagflation-like situation in the UK economy”.

“The specter of stagflation hangs over the UK economy,” said Ed Munk, associate director at investment management firm Fidelity International.

Last month, the Office for Budget Responsibility, the UK’s financial watchdog, said: expected This year will mark the greatest pressure on real household incomes since records began in the 1950s.

Unofficial data in near real-time highlights how consumers are tightening their belts amid a tightening cost of living.

Travel to UK retail and entertainment venues, tracked by Google Mobility Data, has remained flat since mid-February. Consumer confidence fell in mid-April compared with the previous month, according to daily data provided by Morning Consult.

Credit and debit card spending on so-called delayed goods, such as clothing and furniture, remained more than 10% below pre-coronavirus levels in the first week of April, Bank of England data showed. Although not adjusted for inflation.

Most economists expect inflation to rise above 8% in the second quarter after the industry regulator raised the cap on household energy prices in April, and likely to move higher when the cap is revised again in October.

ING economist James Smith predicts the economy will contract by 0.2% to 0.3% in the second quarter as household incomes are squeezed and health sector output slumps due to a drop in Covid-19 vaccinations.

Samuel Tombs, an economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, forecasts a slightly wider contraction and expects the economy to end the year with a growth of just 0.5 percent from February.

“With the economy already close to flattening out, it’s not much time for output to fall for a month or two as the contraction in real household incomes intensifies,” said Ruth Gregory, an economist at Capital Economics.

Thomas Pugh, an economist at consultancy RSM UK, raised the possibility of a recession – defined as two consecutive quarters of contraction.

“With growth expected to average just 0.1% in each of the remaining three quarters of the year, it doesn’t take too much oil price hikes or supply chain disruptions to push the UK into recession,” he said.

That could mean more pain for consumers. Joanna Elson, chief executive of the charity Money Advice Trust, said one in eight British adults reported being without heat, water or electricity in the past three months.

At the end of March, about nine in 10 adults said their cost of living had increased, with about half reducing spending on non-essentials or reducing home energy use, according to an ONS survey.

The drop in real wages could shave around £900 off the average British household’s income this year, according to calculations by economist Jack Finney at consultancy PricewaterhouseCoopers. The income of the lowest earners could fall by as much as £1,300.

Investec economist Sandra Horsfield said savings accumulated during the pandemic should help limit the blow, but these savings were concentrated among wealthier households, “so far, government intervention to support households with little or no savings has relatively limited”.

Silvia Dall’Angelo, an economist at investment management firm Federated Hermes, said the “currently strong” labor market could help ease the slowdown.

However, she added that job growth had slowed and despite Sunak’s announcement of some modest fiscal easing in recent months, “the fiscal stance this year has been generally restrictive”.

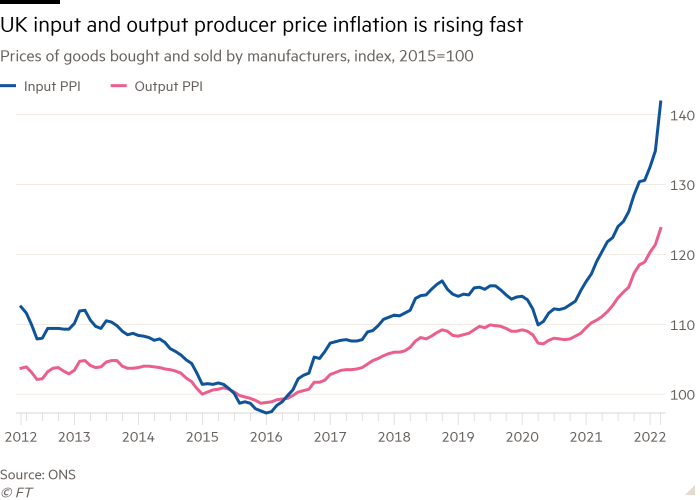

Many companies are also grappling with rising costs and falling demand for goods and services. Input prices for businesses rose at an annual rate of 19% in March, the highest monthly increase since records began 20 years ago, ONS data showed.

Martin McTague, national president of the Federation of Small Businesses, a lobby group, said the faster pace of input price growth compared with consumer price inflation showed “how small business owners are directly hit — — In many cases, reducing their – pay-at-home or scaling back on investment and expansion, rather than passing higher costs on to customers.”

More than four in five managers believe the government is not doing enough to help UK businesses deal with rising costs, according to research by professional body Chartered Management Institute.

Anthony Painter, CMI’s director of policy and external affairs, said businesses were being squeezed as “they face a potential decline in broader consumer confidence, as well as higher material prices, supply chain issues and higher production. cost”.

Sarah Seymour, owner of London-based beauty products company Love Absolute Skincare, said its sales had been hit by people with “less money in their pockets”.

“Sometimes no money comes in at all,” she added. “The battle for survival of a micro-business like mine is real.”

[ad_2]

Source link