[ad_1]

To add to the Biden Administration’s litany of woes: The inflation situation has developed not necessarily to the Biden Administration’s advantage. As we’ll discuss in more detail, an uncomfortably large number of commodities are seeing hefty price increases. For instance:

Here are some price changes since January 2021:

Nat gas +81%

Oil +66%

Agricultural commodities +24%

Rent +13%

Used car prices +44%

Gasoline +36%

Cattle prices +20%

Lumber +15%

Coffee +92%

Hotel Prices +37%Then, today:

CPI: +7.5% pic.twitter.com/r8k2kBCSo5

— Dan Collins (@DanCollins2011) February 10, 2022

A new story in the Financial Times focuses on shrunken inventories in key sectors:

Stockpiles of some of the global economy’s most important commodities are at historically low levels, as booming demand and supply shortages threaten to fuel inflationary pressures around the world.

From industrial metals to energy to agriculture, the rush for raw materials and food staples has been reflected in futures markets, where a large number of commodities have flipped into backwardation — a pricing structure that signals scarcity.

Problems are particularly acute in metals, where spot prices of several contracts on the London Metal Exchange are trading higher than those for later delivery, as traders pay large premiums to secure immediate supply….

Copper stocks at major commodity exchanges sit at just over 400,000 tonnes, representing less than a week of global consumption. Aluminium stocks are also low, as smelters in Europe and China have been forced to cut capacity because of the huge financial strain caused by spiralling energy costs.

As an aside, your humble blogger warned of copper and aluminum shortages in November. Back to the pink paper:

Production cuts are just one factor behind the supply shortages, which have led the Bloomberg Commodity Spot index, a key gauge of raw materials, to rise more than a tenth since the start of the year and hit a record high this month….

Other drivers of the shortages include a lack of investment in new mines and oilfields, bad weather and supply chain constraints caused by the spread of Covid-19.

In other words, some of these results are due to significantly to the direct and indirect effects of Covid: demand whipsawing and supply chain issues due to Covid hitting staffing and cutting throughput. The Covid “recovery” wrong footed many producers. For instance, even though oil production can be dialed up and down, it does not turn on a dime. Automakers were hit by the famed chip shortage, due to slashing orders and then finding that chipmakers had successfully redeployed a lot of capacity to consumer electronics. Automakers, and Therefore buyers, are now having to eat the cost of commodity price increases too.

However, an overarching problem is that, as we saw in the 1970s, an extended period of high energy prices in not too long a period of time propagates through the economy. The oil price jump isn’t anything like what we saw then, and is also nothing like the short but attention-grabbing oil price runup of 2008, where prices briefly peaked at $147 a barrel. We correctly called that that spike (and the increases in other traded commodities) didn’t result from fundamental factors ex China stockpiling diesel for the Olympics, and that was set to fall sharply. A current example of energy prices driving other price hikes:

Traders in Kampala city have blamed the increase in prices of commodities, especially those manufactured from factories, on the high prices of fuel.

Fuel prices started increasing at the beginning of this year and as of now, petrol stands at around sh5070 and diesel at sh4430. pic.twitter.com/jGD7bpHs8w— Baba TV Uganda (@babatvuganda) February 14, 2022

For those cynics who have volunteered in comments that they wonder if Biden is escalating with Russia to divert attention from his Covid and other domestic worries, if that really was a significant motivator, it may not be working out so well. Any polling gains from Biden’s macho show may be more than offset by the incremental increase in inflation in key commodities, particularly energy-related ones. The lead story in the Wall Street Journal is Why Russian Invasion Peril Is Driving Oil Prices Near $100:

The threat of a Russian invasion of Ukraine is shaking up a fragile global oil market, pushing prices closer to $100 a barrel as traders calculate that supplies will struggle to cushion the effect from any significant disruption in Russian fossil fuel exports.

Demand for oil has outpaced production growth as economies slowly rebounding from the worst of the pandemic, leaving the market with a small buffer to mitigate an oil-supply shock. Russia is the world’s third-largest oil producer, and if a conflict in Ukraine leads to a substantial decrease in the flow of Russian barrels to market, it would be perilous for the tight balance between supply and demand.

Those dynamics have led traders in recent days to price in a sizable geopolitical risk premium, according to analysts. Crude oil prices, which haven’t topped $100 a barrel since 2014, jumped to an eight-year high on Ukraine concerns Friday.

And Russia is an important supplier of other key commodities:

“Russia & Ukraine account 4 nearly 1/3 of wheat & barley #exports& about 1/5 of corn #trade. Unrest in the region could keep #prices of these commodities elevated & add to #food costs that are already high” #foodsecurity via @markets https://t.co/0TD7fIItPA via @markets

— Souhad A. (@souhad_16) February 14, 2022

Interestingly, some oil price experts contend that as energy prices have kept rising, “ESG” investors, as in those advocating considering the environment, social, and governance issues in their picks, have been backing away from their former firm positions about fossil fuel divestiture as prices, and stock prices, have rallied:

“I think folks have hidden behind ESG when oil prices were just lower. ESG has gone to the back burner. I’m not saying ESG is no longer relevant but it doesn’t seem to be as important.”https://t.co/tZ5Cx959U7#OOTT #olandgas #WTI #CrudeOil #fintwit #OPEC #Commodities #ESG

— Art Berman (@aeberman12) February 13, 2022

The Financial Times, in another new story, also reports that shale bonds have appreciated, which also means the cost of new debt issuance, has fallen. This development is a blow to US climate change activists. We pointed out years ago that most shale producers were not profitable if oil prices were below $70 a barrel, and that shale gas plays continuing to operate despite that was dependent on them still being able to borrow despite that. From the Financial Times:

Investors are loading up on the debt of US oil and gas companies, lured by their ability to generate cash again as energy prices soar.

Funds now hold overweight positions in high-yield energy bonds compared to a benchmark index, according to Bank of America Global Research. This means that, instead of simply trying to track the proportion of energy sector bonds in the index, investors are choosing to own much more.

Investors’ appetite for energy bonds comes as crude oil prices stage a ferocious recovery, more than doubling since late 2020 to $90 a barrel, their highest in seven years. Natural gas prices have also rallied.

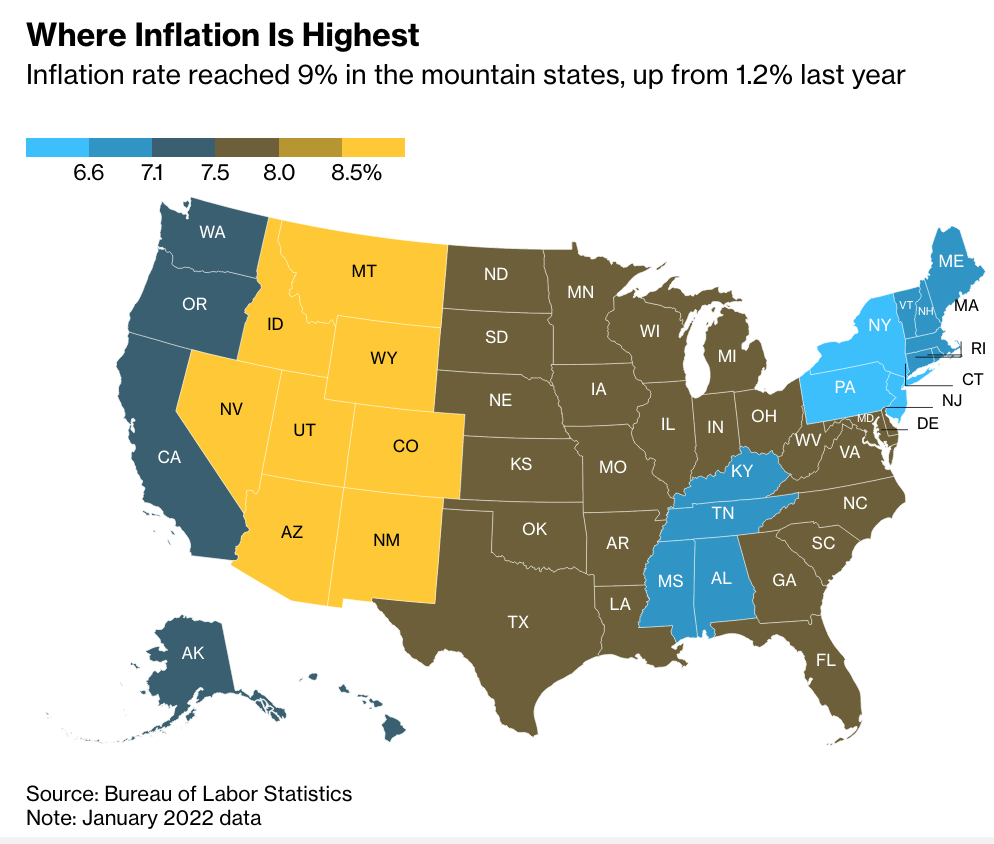

Bloomberg pointed out that in the US, inflation is more pronounced in some areas, with the Mountain states hardest hit:

Even so not everyone is a commodities price bull. Steel is far and away the biggest manufacturing cost input for cars, constituting as much as 47% of manufacturing cost. Consider this end of year steel forecast from Hellenic Shipping News. Even though one could argue that the Omicron caution is overdone, the experts see high steel prices cutting demand by second half 2022:

Steel market participants are becoming increasingly cautious in their purchasing requirements. The forward view on global prices is, gradually, turning more negative, particularly for coil products. The record high values ??reached in the summer of 2021 took many by surprise….

The outlook for the start of 2022 is becoming clouded by yet another wave of Covid-19 sweeping across the globe. The ominous Omicron variant may slow the recovery in the steel market. Many buyers are concerned about a price collapse, in the coming months. Divergent trends, researched across the three regions, are envisaged in the short term….

Reductions in steel selling values ??are predicted in the second half of 2022 across all regions researched. Diminishing growth in flat product consumption, due to the inflated cost of steel and other materials, is anticipated. Inflationary pressure is likely to dampen consumer spending. Moreover, the recovery in demand from the automotive sector is expected to be protracted.

And one can wonder how much high prices will start to crimp demand in other sectors. Many of the commodity categories hit by sticker shock, like copper, energy, and lumber, are important to home building and home renovation. Home prices in some areas are already softening due to higher interest rates; elevated costs for new construction and fix-ups will also affect buyers. And slower activity in such a key sector would slow overall growth.

We haven’t said much about agriculture price rises, but like the other types of commodity price inflation, they aren’t driven by factors the Fed can influence, short of such aggressive interest rate increase that it kills the economy. As Econofact explained in a November 2021 article:

• Meat price changes have been a primary driver of overall food price increases. Changes in meat prices have a large influence in the price indices because consumers spend a relatively high share of their food budget on these items. Beef, pork, and chicken prices are respectively 26.2%, 19.2%, and 14.8% higher in October 2021 than prior to the pandemic in January 2020. Indeed, prices for some meat items have reached the highest levels recorded even after adjusting for overall inflation. The retail price of bacon, for example, was $7.31/lb in October 2020, 36% higher in inflation -adjusted terms than in October 1980. The meat price increases were initially caused by disruptions in supply when packing plants shuttered after workers contracted COVID19. Packing has fully resumed, but there remain extra costs from socially distanced workers and the addition of personal protective equipment. In addition, livestock and poultry feed prices have significantly increased as discussed in more detail below. These increased supply costs have occurred as domestic and foreign consu mer demand for US meat has also been strong.

• Agricultural commodity prices have increased. For every dollar consumers spend on food, about 14 cents reflect the cost of the agricultural commodities at the farm level. Prices for raw agricultural commodities like corn, wheat, rice, and soybeans have risen since the start of the pandemic. The United Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization, Food Price Index, which tracks global prices of commodities used in making food, is up 30% in October 2021 relative to pre-pandemic levels in January 2020. Commodity prices have been rising because of impacts on supply from adverse weather conditions in major crop growing regions (eg, derecho in the United States’ Midwest in Summer of 2020; drought in Argentina, Brazil, and in the Western US in 2021) and from higher input costs like fertilizer and herbicides.

Mind you, higher demand, like higher SNAP payments increasing food spending, and more purchases from abroad, also contributed.

But as you can see, none of these factors are likely to abate soon. Consumers should brace for things getting worse before they might possibly get better.

[ad_2]

Source link