[ad_1]

The world’s poorest country faces a $10.9 billion surge in debt repayments this year after many rejected a deal international relief work Instead, it turned to capital markets to fund its response to the pandemic.

According to the latest data from the World Bank, a group of 74 low-income countries will have to repay about $35 billion to official bilateral and private sector lenders by 2022, a 45 percent increase from 2020.

One of the most vulnerable is Sri Lanka, which ratings agency S&P Global warned last week of a possible default this year as it downgraded its sovereign bond rating. Investors are also worried about countries such as Ghana, El Salvador and Tunisia.

World Bank President David Malpass warned that “the extraction of resources . . . creditors” means “the risk of disorderly default is increasing”.

“Countries are facing a time to recover their debts at a time when they don’t have the resources to pay their debts,” he said.

The increase reflects developing economies taking on more debt to deal with the economic and health-care fallout from the coronavirus, as well as the rising cost of refinancing existing borrowings and a moratorium on debt repayments in the wake of the pandemic.

About 60% of low-income countries need or are at risk of needing to restructure their debt, and a new sovereign debt crisis could emerge, the World Bank warns in its economic forecast Posted last week.

In 2020 and 2021, governments and companies in low- and middle-income countries will issue about $300 billion worth of bonds each year, more than a third higher than pre-pandemic levels, according to the International Finance Association, a financial industry association.

The surge in repayments is on the horizon despite the pandemic boosting a global initiative to ease the debt burden of poor countries. Proved to be a wet squib.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative, launched by the G20 Large Economies Group in April 2020, aims to defer some $20 billion in debt owed to bilateral lenders by 73 countries between May 2020 and December 2020. expanded By the end of 2021, only 42 countries got relief The total amounted to $12.7 billion, according to the Paris Club group of creditor nations, which along with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund helped coordinate the initiative.

Those countries must resume repayments this year and start paying down debts suspended under the program.

At the same time, borrowing costs are rising.

In the first two years of the pandemic, interest rate cuts by the big central banks made it relatively cheap for governments to borrow. But as investors expect global monetary conditions to tighten later this year, it has become increasingly expensive to refinance existing debt.

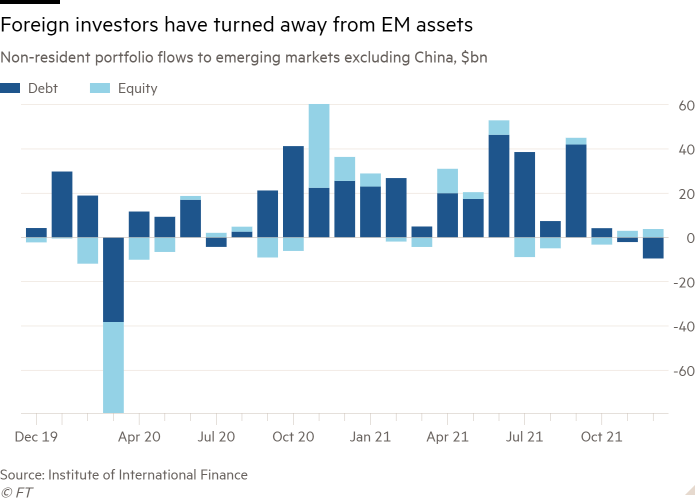

Developing economies, led by Brazil and Russia, have been aggressively raising interest rates for months in response to soaring inflation. But in many countries, interest rates are still below the pace of price growth, and cross-border capital is flowing out of emerging market stocks and bonds.

Ayhan Kose, head of the World Bank’s economic forecasting department, said: “Market access is a wonderful thing when cheap money is available, but as conditions tighten, that may be viewed differently.”

Asset managers, economists and debt activists have all called for new action to ease the debt burden of poor countries.

“The debt problem is growing and the fiscal space of developing countries will continue to shrink. For developing countries, we do risk another lost decade,” UNCTAD Secretary-General Rebecca Greens Rebeca Grynspan said.

Gregory Smith, emerging markets strategist at M&G Investments, said: “Another debt crisis, no matter how triggered, is going to have a very strong impact on countries with high debt levels . . . we have a year or two to design Something to support a country in a systemic crisis.”

The most indebted countries can seek relief from the G20’s plan to replace DSSI. The “common framework” requires participating countries to first reach agreements with bilateral creditors and the IMF, and then obtain the same debt relief from private creditors.

However, critics say this could cut off countries’ access to capital markets. Only Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia have applied, and negotiations have made little progress.

“You know what it means for a country to openly say it has a debt service problem,” Greenspan said. “The private sector will punish them. If a country has any choice, it won’t do it.”

[ad_2]

Source link