[ad_1]

By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Amazon built a warehouse in Tornado Alley, did not build in sufficient protection for workers, denied workers the ability to protect themselves, and is already scheming to cover up its act of social murder.

I’ll prove these four claims in short order, but first, let’s look at how we classify tornados, because we’ll need that to interpret the coverage and the maps that follow. Tornadoes were classified according to the Fujita Scale (F), which was upgraded to the Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF). Here is a chart describing them:

The National Weather Service describes the Edwardsville tornado and classifies it as EF-3:

A strong tornado touched down just to the northeast of the I-270/I-255 interchange at 8:28 PM CST. The tornado moved northeast and intensified rapidly after crossing I-255, striking an Amazon warehouse. The west-facing walls of the warehouse collapsed inward, which was followed by multiple structural failures as the tornado moved through the complex, including the collapse of additional walls and the loss of a large segment of the roof. This was the worst damage along the entire tornado track rated EF-3.

Estimated peak winds were 150 mph. You will note that EF-3 isn’t even the most powerful tornado. Mapping back to the F scale by wind speed, the Edwardsville tornado would be classifed as “considerable damage,” and not as “severe”, “devastating”, or “incredible” (!!) damage.

And yet the Edwardsville tornado, fourth on a scale of six, inflicted damage on the Edwardsville Amazon warehouse like this:

“Considerable,” indeed. The tornado moved right through the warehouse, sparing the north bays, but destroying the south. (North vs. South will become important shortly, when we look at where the deaths took place.)

Amazon Built Its Edwardsville Warehouse in Tornado Alley

The Belleville News-Democrat explains why Amazon sited its warehouse there:

Madison County’s flat, empty land and proximity to interstates, airports, rail and river travel made it an appealing location for the e-commerce giant.

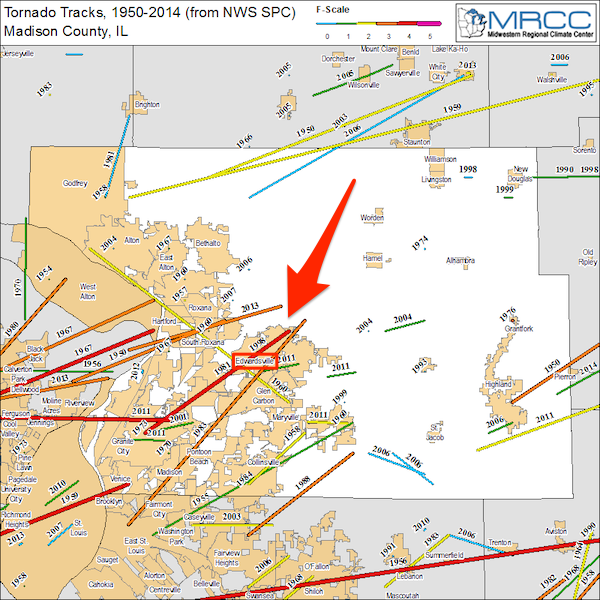

That Edwardsville was in Illinois’ tornado alley did not, apparently, figure largely in Amazon’s plans. From the Midwestern Regional Climate Center:

As you can see, Edwardsville experienced F4 tornadoes in 1911 and 1998, and F3 tornadoes in 1983 and 2011. So the Amazon warehouse has in the crosshairs, and a tornado strike was only a matter of time. One would assume that Amazon would take every measure possible to protect its workers, but sadly, no.

Amazon Did Not Build in Sufficient Protection for Workers

There are three issues with how Amazon built its warehouse. Lack of a basement shelter, tilt-up wall construction, and bathroom storm shelters. Let’s take each in turn.

No basement shelter. As any child in flyover knows — or anybody who’s seen The Wizard of Oz — the safest way to shelter from a tornado is underground, in a cellar. That was not possible in Edwardsvlle. From the Edwardsville Intelligencer:

The Amazon building does not have a basement, which could have offered employees additional shelter.

“As I understand, the challenge here is flooding. You can’t dig very far down before you (reach water),” [Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker] said. “That’s why they don’t allow basements in the industrial area here.”

Presumably, Amazon felt it could offer workers equivalent protection above-ground (unless commercial considerations prevailed, of course).

Tilt-up wall construction. Alert reader Mark Sites describes this construction technique in comments:

The Amazon warehouse appeared to be standard tilt-up construction, the most often used form of construction for big boxes. The the concrete panels are formed on the ground, like a tall skinny rectangle. When the reinforced concrete has reached the needed strength a crane is used to tilt the panels up and ‘stack’ them along the exterior steel frame. The steel framing of the building is what carries the wind loading on the walls. Construction is covered under national and local building codes, which do include wind loads for both walls and roofing, and the procedures for analyzing them.

(I will look into code issues in an Appendix.) If you look back at the picture of the post-tornado warehouse above, you will see the steel framing still standing, amidst the rubble of the walls and the roof. A similar event happened to a Home Depot, a big box like the Amazon warehouse, in Joplin, MIssouri, in 2011. From the Wichita Eagle:

Under high winds, the roof can become compromised, and the panels in tilt-up wall buildings can fall like dominoes, said Larry Tanner, a tornado expert and part of a team of engineers who traveled to Joplin to study the Home Depot collapse and other building failures for the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“Once you lose one (wall) panel, then the dominoes all start to fall, so the failure becomes increasingly more catastrophic,” Tanner said. “I was aghast at how extensive Home Depot’s failure was.”

If the building code had required the Home Depot store to have stronger roof-to-wall connections, it might have sustained less damage, even in such heavy winds, said Tanner and other engineers interviewed by the Star.

“It’s an efficient and low-cost building system, but it’s only stable when all the connections are working,” said Perry Adebar, an engineer who studies tilt-up wall designs at the University of British Columbia. “It’s a bit of a house of cards.”

The Tilt-Up Concrete Association also produced a report on the Joplin disaster, in 2012. It includes this recommendation:

Recommend to ICC and direct to building owners . The TCA should develop specific Tilt-Up based storm shelter designs for winds of up to 200 MPH that would compete against alternative masonry, precast, or cast-in-place designs. Storm shelter design is addressed in 2009 IBC, section 423 and ICC-500.

This implies to me that no Tilt-Up warehouse can withstand a tornado (at least of EF-3 or above. It’s also fair to say that the TCA doesn’t think much of the Wichita Eagle, but given that recommendation, I think the Eagle got the big picture right. So far as I know, that recommendation has never been implemented, by the ICC or anyone else. This brings us to the shelters Amazon actually built.

Bathroom storm shelters. I’ve noticed a dearth of reporting from the majors on how the workers — those who survived, and those who died — actually sheltered. Fortunately, there is local coverage. Here are two accounts from the south side of the warehouse, where the deaths took place. From KMOV, quoting Amazon worker Craig Yost:

“They’re telling people just park your van and go to the shelter,” he said. “Where’s the shelter? The bathrooms? Okay, so I parked the van and go to the bathroom. They had people directing others to the bathroom, and that’s where we sat and waited.”

And then:

“The walls caved in, and I got pinned to the ground by a giant block of concrete,” said Craig Yost. “I was pinned down on my left hip with my right hip and my right shoulder holding a chunk of concrete. On top of my left knee was a door from the bathroom stall, and my head was on that with my left arm wrapped around my head. I could just move my right hand and foot.”

From the Norman Transcript:

When the weather started turning bad, [Jaeira Hargrove and Etheria Hebb] returned and quickly parked their vans. A woman told them to head to the bathroom because of a tornado warning.

Growing up in the St. Louis area, they’d been through warnings before but neither thought they would ever be hit by a tornado, Hargrove said.

They walked to the bathroom, not in a panic.

And then:

“We were just standing there talking. That’s when we heard the noise. It felt like the floor started moving. We all got closer to each other. We all started screaming,” Hargrove said.

Were the bathrooms, as the TCA recommends, “shelter designs for winds of up to 200 MPH”? Clearly not, since winds of 150 mph caused the bathrooms on the south side to collapse, killing people. Bloomberg reports:

One person familiar with Amazon’s warehouse construction said the buildings are designed to local standards that account for events such as severe storms and snow loads. Warehouses in tornado-prone areas include space that is more heavily reinforced with extra steel and concrete where workers are instructed to huddle in event of emergencies, he said.

It would be useful if there were some actual on-the-ground reporting to see how Amazon had those bathrooms constructed. Clearly, the extra steel and concrete, if any, didn’t do the job. Quartz reports:

Amazon did not respond to questions from Reuters about whether its facility’s bathrooms were the designated shelters for tornado emergencies.

It doesn’t matter what Amazon says. We know what the workers said. More:

It was also unclear if the number of bathrooms on the site was sufficient to protect even the 50-plus employees known to be at the site. Amazon has a notorious record of providing fewer bathrooms than necessary for its staff, and for instituting such punishing work schedules that employees relieve themselves in bottles rather than take bathroom breaks.

[I’ve omitted a bunch of Amazon blather from spokesholes at corporate. It’s clear that they’re either lying, or don’t know anything about the material conditions at this particular warehouse.]

Amazon Denied Workers the Ability to Protect Themselves

Amazon did this in at least two ways. First, through poor training. Second, by denying workers cellphones. Let’s look at each of these.

Poor training. From The Intercept:

[A] concern expressed by a dozen Amazon employees who spoke about the lack of workplace safety afforded to workers across the country — not just related to extreme weather events but to hazards in general. Many workers, all of whom requested anonymity to protect their jobs, said they had never had a tornado or even a fire drill over the course of their careers at Amazon, dating back up to six years. Several expressed that they would be unsure of what to do in an emergency. In one case, an Amazon contractor, fearing Hurricane Ida, asked to go home early but was told that leaving would adversely affect their performance quota.

Certainly the vivid description of Amazon straw bosses shouting at workers to head for the bathrooms gives a picture of a training regimen that has been inconsistently, not to say spottily, applied. (And if the workers are contractors, so what?)

No cellphones. From Bloomberg:

An Amazon spokeswoman said company policy currently allows all Amazon employees and delivery drivers to have access to their phones during their shifts. But several workers in different states told Bloomberg their managers had already resumed the ban.

One person whose job entails training new hires said some managers began banning phones to see if doing so caused absenteeism to spike or employees to complain. The people spoke on condition of anonymity because they’re not authorized to speak with the media.

Although the reporting on conditions at Edwardsville is spotty, it does seem that managers were, well, “working toward the Bezos” on cellphone policy:

Five Amazon employees, including two who work across the street from the building that collapsed, said they want access to information such as updates on potentially deadly weather events through their smartphones — without interference from Amazon. The phones can also help them communicate with emergency responders or loved ones if they are trapped, they said.

Indeed, Amazon seems like a pretty schizophrenic company. They can’t train or protect their workers, but they’re brilliant with technology:

Amazon can

? track every milisecond a worker is “off task”

? use heat maps to prevent workers organizing

? monitor how many times a driver blinks

But says it can’t

? tell rescuers how many workers were there and need to be searched for

Yeah right #AmazonTornado

— ResistHere (@ResistHere) December 12, 2021

Amazon Is Already Covering Up

From the Intercept:

The company took an additional step yesterday by encrypting internal help ticket messages about the Illinois facility, making them inaccessible to most workers, according to an employee who provided screenshots before and after the messages were encrypted. Amazon did not respond to a request for comment on why the records had been encrypted.

One can only wonder why. More:

The messages revealed a communication breakdown in which corporate failed to notify employees about the tornado even as it happened. “Corporate and IT were troubleshooting network outages and found out the building was hit by a tornado from the media,” said the employee who provided the communications. “What the correspondence showed was that initially, nobody knew what was happening. More and more people joined in on the tickets to troubleshoot the issues only to find out from the media that the building was hit by a tornado.”

The narrative was “absolutely heartbreaking,” the employee added. “It looks like they had almost no warning.”

Conclusion

Friedrich Engels coined the phrase “social murder” in 1845. It’s still germane today! From “The Condition of the Working Class in England“:

When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live – forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence – knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains.

That Amazon found out its warehouse had been destroyed by a tornado because corporate was troubleshooting a network outage…. Well, that pretty much sums up an offence by omission. These executives were very different from Amazon worker Clayton Cope, who gave his life trying to save others.

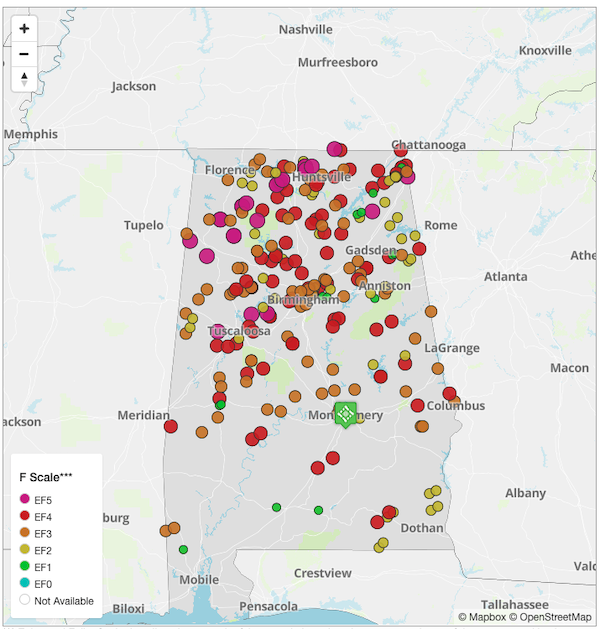

At this point, we recall that the NLRB gave the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union a do-over in its attempt to organize workers at Bessemer, AL because Amazon — hold onto your hats here, folks — cheated. Alabama, just like Illinois, is in a tornado alley. From the Montgomery Advertiser:

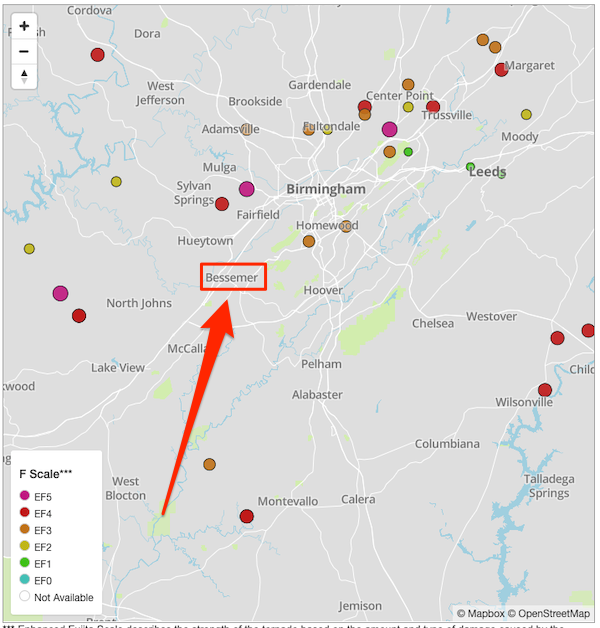

And Bessemer, just like Edwardsville, is in tornado alley:

(It is true that Bessemer’s EF-5 was in 1977, its EF-4 in 1956, and its EF-3 in 1967. But just as in Edwardsville, it’s only a matter of time. As the first map, shows, Alabama has tornadoes aplenty.

So, will the Bessemer Amazon workers be adding hardened tornado shelters to their list of demands? How about training, and cellphones on the floor?

APPENDIX 1: Amazon Executives Behaving Badly

Oh, come on (1):

Thoughts and prayers going out to our team in Edwardsville tonight and thank you to all the first responders.

— Dave Clark (@davehclark) December 11, 2021

Oh, come on (2):

Jeff Bezos: “This football when you bring it back down to Earth, is going straight to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.”@michaelstrahan: “If I fumble this ball…it’s just going to float!”#BlueOrigin

LIVE UPDATES: https://t.co/EoDkjYiYhd pic.twitter.com/BVKpPaobpO— ABC News (@ABC) December 11, 2021

APPENDIX 2: Building Codes for Tornado Shelters

From the Edwardsville Intelligencer:

“We know that the building was constructed according to and we want to go back and look at every aspect of this,” [Kelly Nantel, director of national media relations for Amazon] said.

As a wise man once said: “The nice thing about standards is that you have so many to choose from.” In any case, the question of what standard the Amazon bathroom storm shelters were built to is, at this point, an open one. (It would be nice if some enterprising reporter could find out.). We do know one thing about building codes in general. Again from the Kansas City Star:

Some engineers interviewed by the Star said building codes for big-box stores need to be strengthened, or the stores should have internal storm shelters when they’re built.

said Tim Reinhold, chief engineer at the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, which does research for the insurance industry. “Engineers know they are competing for the minimum building code, and so they design right to them.”

Of course, Amazon has all the money in the world, so they don’t have to design to the lowest common denominator. Unless commercial considerations prevail, of course.

Be that as it may, I discovered that the City of Edwardsville uses the International Building Code (2006), which I downloaded. The word “tornado” does not appear. Nor does the phrase “storm shelter.” The individual words “storm” and “shelter” appear in irrelevant contexts (like “storm door” and “bus shelter”). So I am at a loss. Perhaps that enterprising reporter will interview Edwardsville’s code enforcement officer and find out what standard was applied to Amazon’s bathroom shelters; presumably some sort of record was kept by the general contractor, as well.

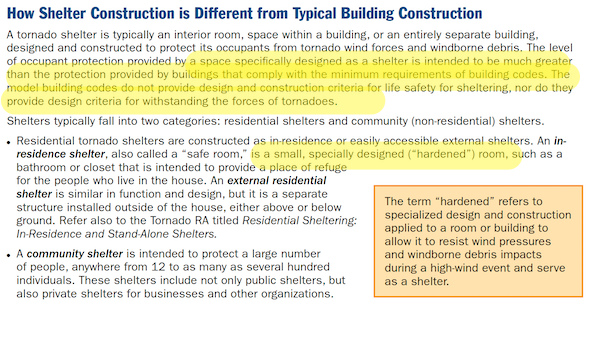

Until then, all we can do is guess. Here is the standard that FEMA recommends:

It does seem, however, that even Amazon (and Edwardville Code Enforcement) followed FEMA’s guidance, the “hardened” “specialized design and construction” was insufficient.

There is also ICC 500, a standard produced by the International Code Council (“the leading global source of model codes and standards and building safety solutions”). From Chapter 7 of ICC 500, “Storm Shelter Essential Features and Accessories“:

This standard is extremely amusing, first because of 702.2: “All exposed components and cladding assemblies and roof coverings of tornado shelters shall meet the standards of the applicable code,” which I — readers will correct me — interpret to mean that the roof and the walls shall conform to local building codes, whatever they may be. The rest of the section concerns itself with the internals of the shelter, like wiring and lighting. 702.3 is also amusing, because you can see that if Amazon situated the shelter within a bathroom, its compliance with the minimum number of water closets and laboratories is 100%.

Finally, OSHA has this… thing, whatever it is (it doesn’t read like guidance). From “Tornado Preparedness and Response“:

Identifying Shelter Locations

An underground area, such as a basement or storm cellar, provides the best protection from a tornado. If an underground shelter is unavailable, consider the following:

- Seek a small interior room or hallway on the lowest floor possible

- Stay away from doors, windows, and outside walls

- Stay in the center of the room, and avoid corners because they attract debris

- Avoid auditoriums, cafeterias and gymnasiums that have flat, wide-span roofs.

We don’t know, of course, how the “rooms” were constructed. From the reports of the workers, “a heavy concrete floor or roof system overhead” seems unlikely. Once again, an enterprising reporter could determine conditions on the ground. Or perhaps the nature of the roofs over the bathrooms on the south side could be doped out from aerial photography.

[ad_2]

Source link