[ad_1]

I have been emphasizing the Fed’s dilemma: if it raises interest rates, it will increase the cost of debt servicing in the United States. 100% debt to GDP means that 5% interest rate translates into 5% of GDP additional deficit, which is a high interest rate of US$1 trillion per year. If the government does not tighten this range immediately or reliably in the future, then higher interest rates will eventually increase rather than reduce inflation.

Jesper Rangvid points out The European Central Bank’s problems are worseRecall that in a euro crisis, Italy seems unable to roll over its debts and default. Mario Draghi promised “at all costs”, including buying Italian debt to stop it, and did it. But Italian debt now accounts for 160% of GDP, and the European Central Bank is still buying Italian bonds. What if the European Central Bank raises interest rates in an attempt to slow inflation? Well, Italy’s debt solvency has soared. An interest rate of 5% means that 8% of GDP is used to service debt.

The central bank first stopped buying bonds and then raised interest rates. Whether the U.S. bond purchase program actually reduces the yield of Treasury bonds is still controversial. But there is no doubt that the European Central Bank’s bond purchases depress Italy’s interest rates by reducing the risk/default premium of that interest rate. If the European Central Bank ceases to purchase or cancels its promise to purchase at all costs, debt servicing costs will rise again, thus accelerating the cycle of doom.

jasper:

The European Central Bank is in a dilemma.

The European Central Bank knows that a very expansionary monetary policy, coupled with already high inflation and strong economic growth, will create a serious risk of out-of-control inflation and inflation expectations.

However, the European Central Bank also knows that if it tightens monetary policy, that is, stops asset purchases and raises interest rates, the debt-laden Eurozone countries will face severe challenges.

Take Italy as an example. At the end of last year, Italy’s public debt was equivalent to 160% of Italy’s GDP. This is a large debt. …

Low interest rates have always been kind

Although the debt burden has increased by 50%, Italy’s debt service costs have been reduced by one-third from 2007 to 2020. The reason is of course low interest rates.

…In addition to the decline in global interest rates, the European Central Bank has been buying large amounts of euro zone government bonds, further reducing interest rates significantly. …

| Figure 11. Italian debt securities held by the European Central Bank. Millions of euros. Source: Data stream from Refinitiv. |

The European Central Bank bought a lot of debt. First, it is related to the Public Sector Procurement Plan (PSPP) launched after the Eurozone debt crisis, and secondly, it is related to the Epidemic Emergency Procurement Plan (PEPP), which was launched in response to the new crown crisis. According to the PSPP, the European Central Bank has accumulated 400 billion euros worth of Italian debt. Under PEPP, it has accumulated 300 billion euros. The European Central Bank holds a total of 700 billion euros of Italian debt, as shown in Figure 11. The European Central Bank owns nearly 25% of all outstanding public debt in Italy.

|

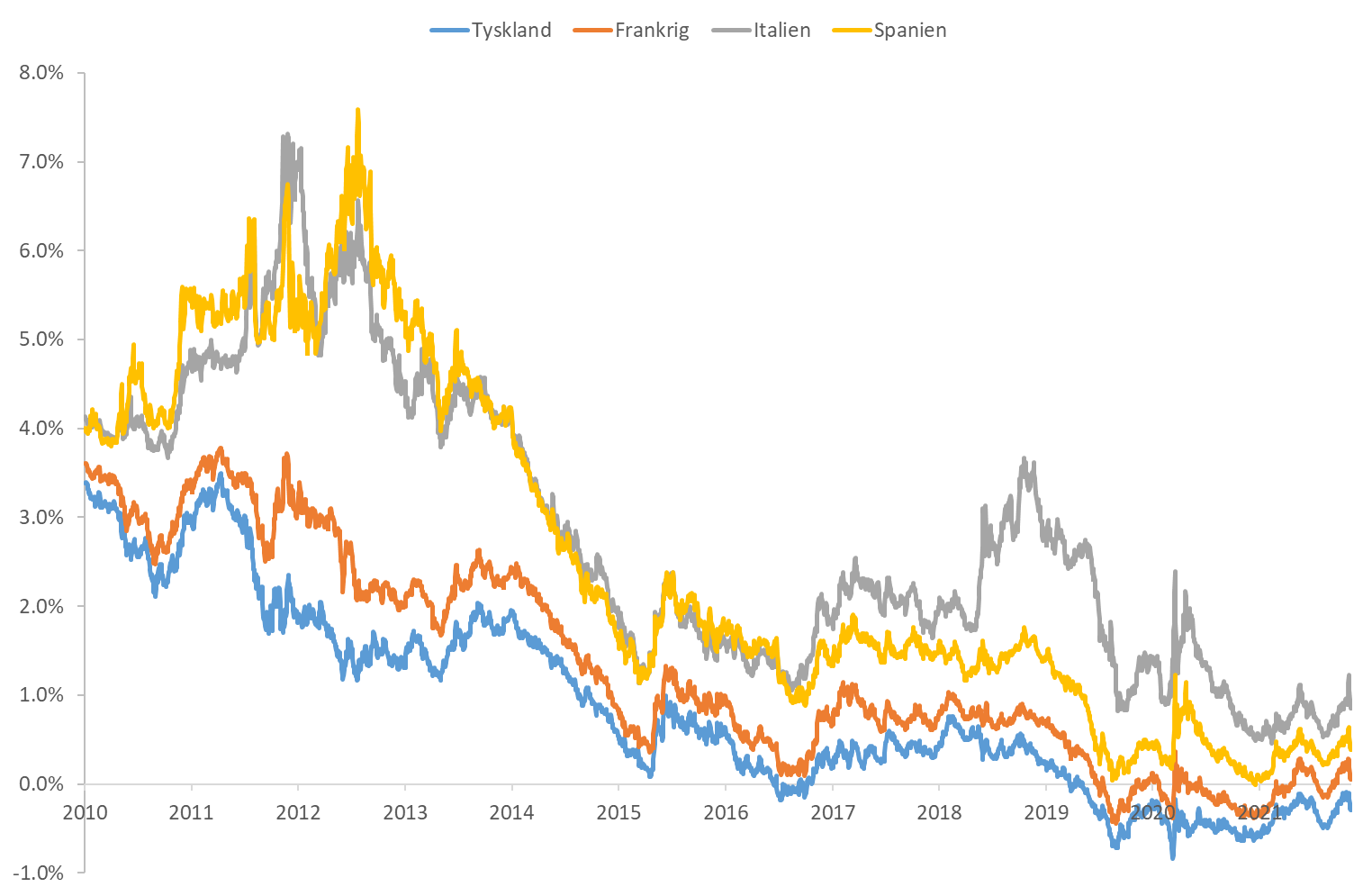

| Figure 12. Yields of long-term Eurozone government bonds. Source: data stream from Refinitiv |

Many of us remember the Eurozone crisis of 2010-2013. Italy’s rate of return reached more than 7% in 2012, as shown in Figure 12. It wasn’t until Mario Draghi delivered his famous “We Will Do Anything” speech in 2012 that the rate of return declined (link). The European Central Bank rescued Italy and thus the Eurozone.

This is an important reminder that it may happen. For the United States, the huge default/inflation premium of real interest rates is a theoretical possibility. If this event is interpreted as a fear of returning to inflation, or as a memory from the 1790s, then it may be from the early 1980s. memory. For Europe, this happened 10 years ago.

Jasper did not mention an interesting question about what will happen to all these bonds on the ECB’s balance sheet, or if Italy’s spreads widen again, it will certainly buy bonds in the event of a default.

Jasper also didn’t mention a small piece of good news. I think Italy’s debt is longer than that of the United States, even though I don’t have a good figure on hand. This fact means that higher real interest rates (including default premiums) will only slowly diffuse into interest costs.

In total,

The European Central Bank is in trouble. Regardless of whether people are worried that this round of inflation will continue, the fact that the European Central Bank is constrained by fiscal considerations is problematic. If the European Central Bank needs to raise interest rates one day, it will face the aforementioned dilemma.

what to do?

What is the solution? In this blog, this will take us too far, but it exists in the old discussions of macroeconomic reforms in certain European member states, leading fiscal policy on a healthy path, increasing productivity and competitiveness, and ultimately achieving Higher growth. This is easier said than done.

Draghi knows very well that “at all costs” is a stopgap measure to provide Italy with room for structural and fiscal reforms. Those (foreseeable?) didn’t happen, so here we are again. Is it too late? Italy will certainly not carry out reforms before the crisis, so the situation must be so serious that the crisis will eventually stimulate a growth-oriented economy.

However, the European Central Bank is still between difficulties and obstacles. If the Fed tries to raise interest rates substantially, it will do so.

[ad_2]

Source link