[ad_1]

In Gwadar, a developing port city in southwestern Pakistan, since 2015, Adam Qadir Baksh (Adam Qadir Baksh) has been hoping that his auto parts business can make a major leap, but without China’s promises In the case of important tailwinds, none of this has been achieved.

“The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor will not benefit local component suppliers and other suppliers,” Bakshi said.

His dissatisfaction dates back to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Pakistan six years ago and the official launch of bilateral infrastructure development projects under the “Belt and Road” initiative. Bakshi said that Pakistan did not benefit from it because almost everything in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project was imported from China.

“China only purchases sand and gravel locally for construction projects,” said Nasir Solabi, chairman of the Gwadar Rural Community Development Committee. “All other raw materials are imported from China, leaving very little for the local industry.”

CPEC is a component of a flagship BRI valued at US$50 billion, including power plants, industrial clusters, and road and rail upgrades. About half of China’s pledged funds have flowed in through investment and inter-governmental loans, driving Pakistan’s economic growth in 2017 and 2018 by more than 5%. But those who have not benefited from China’s generosity are losing hope and becoming restless.

Since November 15, thousands of locals have sat in protest and blocked the main road to Gwadar Port. They require basic amenities, including water and electricity, as well as access for fishermen to go to sea. “If our requirements are not met, we will close CPEC,” local leader Molana Hidayat said in a belligerent speech.

Pakistan’s foreign direct investment from China has declined. According to data from the National Bank of Pakistan, the country’s central bank, China’s FDI for the quarter ended September was only 76.9 million U.S. dollars, compared with 154.9 million U.S. dollars in the same period last year.

FDI in the fiscal year ending in June also dropped significantly. In the 2019 fiscal year excluding the general election, the total inflow was US$757 million, the lowest level since 2015. In most years, China’s FDI accounted for 30% to 50% of Pakistan’s total, so the downward trend is a warning light for the country’s economy.

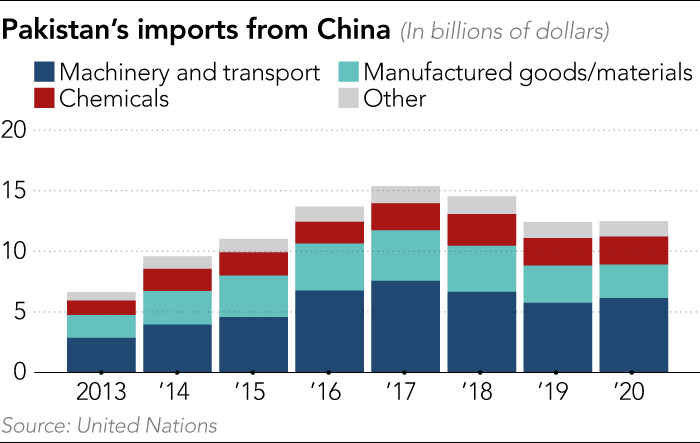

China’s economic slowdown is also evident in Pakistan’s trade data. United Nations data shows that China’s exports to Pakistan have been declining since reaching a peak of US$15 billion in 2017. The downward trend of manufactured products and materials is obvious. Steel—essential to infrastructure development—has seen an overall decline of 40% between 2016 and 2020.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, touted by former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif as a “game changer”, helped solve Pakistan’s severe power generation shortage.

According to Mosharraf Zaidi, CEO of Tabadlab, a think tank based in Islamabad, CPEC has also had a profound impact on cities and road traffic, and helped build many roads connecting villages. He told Nikkei Asia: “None of Pakistan’s bilateral partners have played a central role in the country’s economic story like China and the CPEC framework.”

This article is from Nikkei Asia, A global publication with a unique Asian perspective on politics, economics, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and external commentators from all over the world share their views on Asia, and our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of the 300 largest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside of Japan.

However, some projects have stalled, including the Route 1 railway project, which is the most expensive component of CPEC and cost US$6.8 billion to upgrade the Karachi-Peshawar railway line. China originally planned to provide US$6 billion in loans to the program, but the differences between the governments of the two countries lasted for more than a year and remained unresolved. The project was not affected.

This dissonance is not new, but it is usually done behind closed doors. However, China’s grievances are occasionally leaked.

In early 2019, the then Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan Yao Jing met with officials of the Balochistan government in Quetta. Although never officially confirmed, he is extremely picky. According to a person attending the meeting, he said: “You have not taken seriously the delay in issuing a permit to a Chinese company to start construction of a coal-fired power plant in Gwadar.”

This rift between the two parties has become more apparent, leading to a reduction in Chinese investment and exports to Pakistan.

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif speaks at the CPEC inauguration in Gwadar Port in November 2016 © Caren Firouz/Reuters

Islamabad is shocked by the high cost of the Chinese project. Former Prime Minister’s Special Assistant to Power and Petroleum, Tabish Gauhar, stated in the Cabinet of Pakistan in August that the CPEC power project is 25% more expensive than international standards.

“The Chinese ambassador complained to me that you destroyed CPEC and did not do any work in the past three years,” said Salim Mandeviwala, chairman of the Senate Standing Committee on Planning and Development, at a committee meeting in September. Officials and officials defended 135 Chinese companies operating in Pakistan.

“In general, China has become more cautious with Pakistan,” James M Dorsey, a senior researcher at the Rajaratnam Institute of International Studies in Singapore, told the Nikkei Shimbun. “As many investors do, they pay more attention to return on investment than before.”

Dorsey believes that with the Covid-19 pandemic and ongoing trade disputes, China’s turning point will appear in early 2020. He believes that another important reason is that more and more foreign governments are unable to keep up with the pace of repayment.

Other factors may cause an economic slowdown. Power generation is an example. With the launch of the new power plant, Pakistan’s installed capacity has reached nearly 40,000 MW, while peak power demand is 25,000 MW.

Terrorist attacks against China’s interests have also had a chilling effect on economic cooperation. Recently, nine Chinese citizens were killed by terrorists near the Dasu Hydropower Project in northwestern Pakistan.

Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Program at the Wilson Center in Washington, has no doubt that Beijing’s security issues have affected investment. “The truth is that China’s goals are constantly being hit, even after Beijing has expressed concerns and called for increased security,” he told Nikkei.

Pakistan’s slow response has inhibited China’s interest in new projects. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan’s chaos in August and the Taliban’s return to Kabul may exacerbate uncertainty.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor promotes the development of road connections between Gwadar and Quetta, the capital of Balochistan. This reduces travel time and should provide opportunities for Gwadar transportation companies.

Muhammad Arif, general manager of Quetta Al Safeer Public Transport Company, said: “The passenger business in Gwadar has performed well for many years.” “However, none of us has taken advantage of cargo transportation opportunities because so far, Gwadar Port Failed to start.”

Ilyas Khan, who works for another local transportation company, said: “There are few opportunities to transport goods, mainly for transit trade in Afghanistan, but the transporter does not get any major business from the freight business at the port.”

“We expected a large amount of goods to be shipped out of Gwadar Port. We placed hopes on developing our business, but these expectations did not become reality,” he said.

The development of Gwadar Port failed to meet the expected freight level ©Aamir Qureshi/AFP/Getty

Jeremy Garlick, associate professor of international relations and China studies at the Prague University of Economics and Business, agrees that China is becoming more cautious about investing in Pakistan. “Given the current global tensions and the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, I think we are likely to see a continued slowdown in Chinese investment in the next few years,” he told Nikkei.

Since the establishment of CPEC in 2015, Chinese investment has been crucial to Pakistan’s economy. In addition to alleviating power and connectivity issues, Pakistan is also using Chinese funds to repay other lenders, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

At the same time, observers worry that China’s capital inflows may contribute to the economy’s dependence on more and more CPEC projects.

In the quarter ending in September, the decrease in China’s FDI coincided with the increase in FDI from the United States. In three months, it jumped four times to reach 100.9 million U.S. dollars, while China halved to 76.9 million U.S. dollars.

Experts believe that it is too simple to interpret it simply as the US’s move to replace China. Due to past experience and Pakistan’s long-term cooperation with China, Garrick did not see any signs that the United States was preparing to increase investment in Pakistan. “If it cannot obtain funding from Beijing, Pakistan will have to find funding elsewhere,” he said.

“U.S. officials have long tried to treat U.S. investment in Pakistan as a fairer and more sustainable alternative to Chinese projects,” Kugelman said. Nevertheless, he believes that China can provide investment and loans faster, more adequately, and with fewer conditions than the United States.

“Let us be clear, it is unbelievable to assume that the United States can replace China’s capital in Pakistan,” he said.

Kugelman believes that Washington also knows that it cannot change Sino-Pakistani relations. “It cannot get Pakistan out of China,” he said. “Unlike many countries in this region and other regions that seek China’s economic support but are not firmly standing in the Chinese camp, Pakistan has a deep ally with China.”

China and Pakistan still regard India as a common enemy. China hopes to have a friendly neighbor in its south, while Pakistan seeks the blessings of a non-transactional global power, as Pakistani officials believe.

Chinese President Xi Jinping (right) meets with Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan in Beijing in April 2019 © Madoka Ikegami/Pool/AFP

Can Pakistan revive China’s interest and investment? A Pakistani official did not think so.

“With the end of the early harvest phase of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, China-led infrastructure construction has reached its peak in Pakistan,” a government official who asked not to be named told Nikkei Shimbun.

“CPEC is not over yet, but in the remaining nine years, we cannot expect to see a small part of the infrastructure development that occurred between 2015 and 2020,” the person said.

A version of this article First published by Nikkei Asia on November 30, 2021. ©2021 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved

Related stories

[ad_2]

Source link