[ad_1]

This is Naked Capitalism Fundraising Week. 1,552 donors have invested in our efforts to fight corruption and predatory behavior, especially in the financial sector.Please join us and participate through our Donation page, Which shows how to donate via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal.read Why we do this fundraising event, What we achieved last year, And our current goals, More original reports.

Lambert is here: The title should be “Doing Better”, not “Doing Better”. Some people would say that all capital is human capital. Perhaps the term “human capital accumulation” will not be so harsh…

Authors: Simeon Djankov, Policy Director, Financial Markets Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, and Eva (Yiwen) Zhang, Researcher, Peterson Institute for International Economics. Originally published on VoxEU.

Excluding human capital from policy discussions may lead to incorrect inferences about which measures are most successful during a pandemic. The authors of this column are based on a sample of 45 mainly OECD economies and show that during the Covid crisis, high levels of human capital and flexible labor supervision have enabled the labor force participation rate to recover more quickly. Countries that are prepared to combat the effects of globalization and robotics have also managed to mitigate the impact of the shock on the labor market.

Baldwin and Forslid (2020) argue that in countries with sufficient human capital, the labor market is stronger because highly skilled workers are more likely to have flexible work arrangements. During periods of social distancing and lockdown measures, high-skilled jobs can also be more easily adapted. If this assumption is correct, then in countries with higher human capital, labor force participation will recover faster after COVID-19. We found that this was indeed the case in a sample of 45 predominantly OECD economies in the first year of the pandemic (Figure 1).

figure 1 Countries with higher human capital recover faster

notes: The change in the labor force participation rate is measured between the second quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2021. We use indicators to measure the accumulation of human capital to measure the share of free high-skilled jobs that are likely to be transferred to other countries or regions to lose to robots. The sample includes 45 economies that provide quarterly labor force participation data: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden , Switzerland, the United States and Vietnam.

source: The author uses the calculation of Angrist et al. (2021) The data set and the labor force participation rate measured by the OECD, last interviewed on October 30, 2021.

Other more traditional forces may also play a role in the work recovery process. Since the 1980s, labor supervision in most parts of the world has become more flexible (Blanchard et al., 2013). The impact of this dynamic has been the subject of many empirical studies, especially in the European context. For example, Bjuggren (2018) found that the 2001 reforms that increased the flexibility of the Swedish labor market also increased participation. Bentolila et al. (2012) showed that flexible labor rules have reduced the wide labor market gap between insiders and outsiders in southern European economies. Kuned et al. (2016) The use of OECD data shows that relaxation of employment regulation is conducive to employment transformation, thereby increasing labor force participation. Botero et al. (2004) uses global data sets to show that flexible labor supervision allows workers to engage in formal work and increases labor force participation.

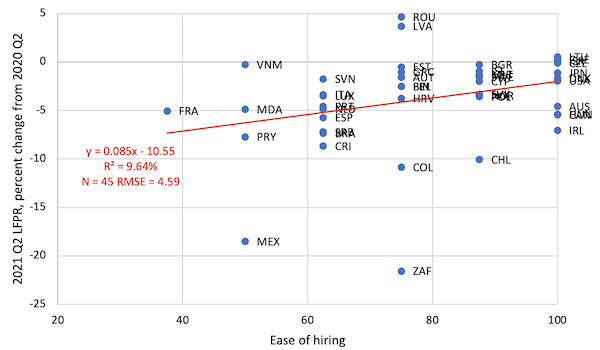

We find that the hypothesis that the flexibility of labor market regulation contributes to employment recovery has some support. In particular, there is a positive correlation between the percentage change in the labor force participation rate in the first year of the pandemic and the regulatory index of ease of hiring (Figure 2).

figure 2 Countries with flexible recruitment regulations recover faster

notes: The change in the labor force participation rate is measured between the second quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2021. The analysis is based on the data on the difficulty of hiring before the 2019 pandemic, especially the fixed available time and the longest term-long-term contracts for long-term tasks. The sample includes 45 economies that provide quarterly labor force participation data: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden , Switzerland, the United States and Vietnam.

source: The author uses the updated calculations of Botero et al. (2004) Data set and labor force participation rate measured by the OECD, last interviewed on October 30, 2021.

We used regression analysis to further test the human capital and regulatory flexibility assumptions. There is a significant positive correlation between human capital and the faster recovery of labor force participation. This is indeed the case when controlling per capita income and the convenience of recruitment supervision. If we control other flexible labor supervision agents, these qualitative results will remain unchanged.

The coefficient of labor supervision is positive, but it is not statistically significant. The interaction between regulation and human capital is negative, but not significant. Overall, the results show that high levels of human capital and flexible labor supervision enable labor participation to recover more quickly during the crisis. However, the influence of the former is major. Regardless of the level of regulation, countries that are prepared to deal with the impact of globalization and robotics have also managed to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the labor market.

Policy advisers should pay attention to this result because it may distort inferences about which labor market policies have produced positive results during a pandemic. Initial conditions play an important role in designing such policies, both in terms of regulation and human capital accumulation as pointed out in this column.

[ad_2]

Source link