[ad_1]

This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1384 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, more original reporting.

Yves here. So many simmering and hot conflicts, and so little time to make sense of them. So thank the War Nerd, Gary Brecher, and Mark Ames for letting us have first dibs on an update of an September post, when the media started kinda-sorta paying attention to the Tigray-Ethiopia conflict.

By Gary Brecher, the nom de guerre-nerd of John Dolan. Buy his book The War Nerd Iliad.Hear him read his comic memoir Pleasant Hell in audiobook format. To read more Radio War Nerd newsletters, subscribe to the RWN podcast at patreon. This is a repost of a Radio War Nerd newsletter originally published September 21, 2021, and updated on November 15 for this article.

Ethiopian POWs paraded through Mekelle

The big news sites have finally started to do some serious reports on the war in Tigray, but there’s a funny tilt to their coverage: they’re not very interested in the war aspect of the war, if you know what I mean. There are a few honorable exceptions, but looking back at mainstream coverage of this war, it’s odd how little there is about actual combat. This happens a lot with African war stories, as if the MSM can only think of African war as atrocities, not as strategy and tactics. I’m not minimizing the atrocities, but as I’ve said a lotta times, atrocities are part of war-fighting everywhere, just as publicizing and hiding them is part of overall strategy.

Most people by now understand that there’s been terrible suffering in Tigray. That too is true of every war. And though it’s a good idea to draw attention to civilian suffering, what happens on the battlefield still decides the outcome. In Syria, for example, the pro-‘rebel’ MSM won the media war, no contest. But the SAA/Hezbollah/Russian side went and won on the battlefield, nullifying the efforts of thousands of hard-working propagandists from NYC to Ankara.

In fact, it makes much more sense to fold atrocities and propaganda into the category of war-fighting than to take them as if they were just tragic events unconnected with real strategy. This is especially true in the Ethiopian wars of the last four decades, which have never gotten the respect they deserve for the sheer ferocity and brilliance with which they were fought.

That’s true for this latest episode of the Ethiopian long war, the one that flared when the Ethiopian and Eritrean armies tried to sandwich Tigray between them in November 2020. This war was a typical war in the Horn, with uniformed armies deploying infantry, artillery, armor, and aircraft (both piloted and drones.) Yet it’s hard to find stories about what happened on the battlefields. When the war started, I thought there would be more video of the battles, since everyone has a camera phone and a Twitter account. But the Ethiopian gov’t came up with a simple plan to stop anyone filming its wet work in Tigray, cutting off all wifi from Tigray and locking down the borders. I wrote about how well this worked in a newsletter for the Radio War Nerd podcast .

The short version is, it worked. Although, you can’t help but wonder if it would’ve worked quite as well if there’d been a lot of interest from the people who run the big news organizations. Bans like this work a lot better when the rich consumers aren’t very hungry for news anyway.

The mainstream narrative was simple: in early November 2020, the ENDF (Ethiopian National Defense Force) moved into Tigray and crushed the Tigrayan rebels within a few days. The Tigrayan leadership said they were retreating to the hills to fight a guerrilla war, but we’ve heard those stories too often to take them seriously. It was over and the ENDF had won.

So it was a giant surprise, the biggest military surprise in years, when on June 28, 2021—just seven months after the supposedly powerful ENDF rolled through Tigray–the Tigrayan Defense Force (TDF, formerly TPLF), the rebranded military force of the TDLF (Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front), reconquered the Tigrayan provincial capital Mekelle, marching in with thousands of Ethiopian and Eritrean prisoners.

How did that happen? Let’s go back to the Battle of Adwa, another shock victory that happened in Tigray in 1896. In that battle, an Ethiopian force cut an Italian army to pieces. That wasn’t supposed to happen either. An African army had destroyed a large European force. Many people remember Japan’s victory over Russia as the moment when the rest of the world realized European armies could be beaten by non-Europeans, but in much of the world Adwa meant even more.

Adwa is a Tigrayan town northwest of Mekelle so, as you might expect, it came back into military news as soon as the war began. On November 20,2020, Al Jazeera reported that the ENDF had taken both Adwa and Axum.

Adwa and Axum! You couldn’t imagine a more illustrious, familiar pair of cities to pop up in war news. They’re like those Belgian towns that were battle-sites every few summers during the 16th-21st centuries. The names of those Belgian towns came up so often, yet were so difficult for both British and French poets to use, that Matthew Prior, one of the war poets of 17th-c. Britain, mocked them in a poem on the British victory at Blenheim:

What work had we with Wageninghen, Arnheim,

Places that could not be reduced to rhyme?

And though the poet made his last efforts,

Wurts — who could mention in heroic — Wurts?

Prior’s poem is an apostrophe to his counterpart, Boileau. As you can see in the quoted lines, Prior is very collegial, basically having a post-game beer with Boileau, gloating but at the same time sharing the misery they both went through trying to find a way to incorporate un-heroic place names like “Wurts” into their bread and butter, which was providing patriotic verse as required.

TDF guard and possible future war poet getting in some reading

There are probably poets writing in Tigrinya and Amhara right now, trying to work Tigrayan place names into their war poems. And when the current iteration of this very long war stops for a while, they may well josh each other over a bottle of Habesha about the problem of working “Jijiqe” or “Adigrat” into their rhyme-schemes (the fact that there were massacres in those places may not matter as much as some might think. Places described as ‘war-torn’ develop an excellent and very dark sense of humor).

So, two weeks into the war, the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) announced it had captured the very heart of Tigray. It sure looked like the war was over.

But there was another precedent that should have warned us not to be too quick in calling the fight for the favorite: the great Battle of Afabet in the spring of 1988, in which a huge, mechanized Ethiopian force was annihilated by Eritrean guerrillas from the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF).

At that time, the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) were allied to the EPLF, and were the most effective of the Ethiopia-based groups. The war against the Derg was won by a coalition of many militias, but only these two really had much combat power—and both were dominated by ethnic Tigrayans.

There’s not a clear ethnic divide between the elites of Eritrea and Tigray, though they’re now enemies. The Eritrean elite is mostly ethnically Tigrayan. In fact, the EPLF, the victorious Eritrean insurgent force, started as a force dominated by highland-Christian Tigrayan Eritreans. Their first victory was not against Ethiopia but their rivals, the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), a Saudi-backed movement led by lowland, coastal Eritrean Muslims.

Tigrayan domination of Eritrea goes right to the very top. And the top, in Eritrea, consists of one very scary guy, Isias Afwerki. He doesn’t want it advertised, but he’s from an aristocratic Tigrayan background.

Isias Afwerki: He might be the real winner of this war.

There’s a simple lesson here: Tigrayans are the bulk of combat power in the Highlands of the Horn. You’d think that would lead to the conclusion that you shouldn’t mess with Tigray unless you’re ready to get in a long, nasty war, even when the conventional military wisdom is that the Tigrayans don’t have a chance. They weren’t supposed to have a chance against the Europeans in 1896, either–or the Ethiopian Derg in the 1980s. If you’re running a war-nerd bookmaking business, put a sign on the window: “No bets on wars in Tigray.”

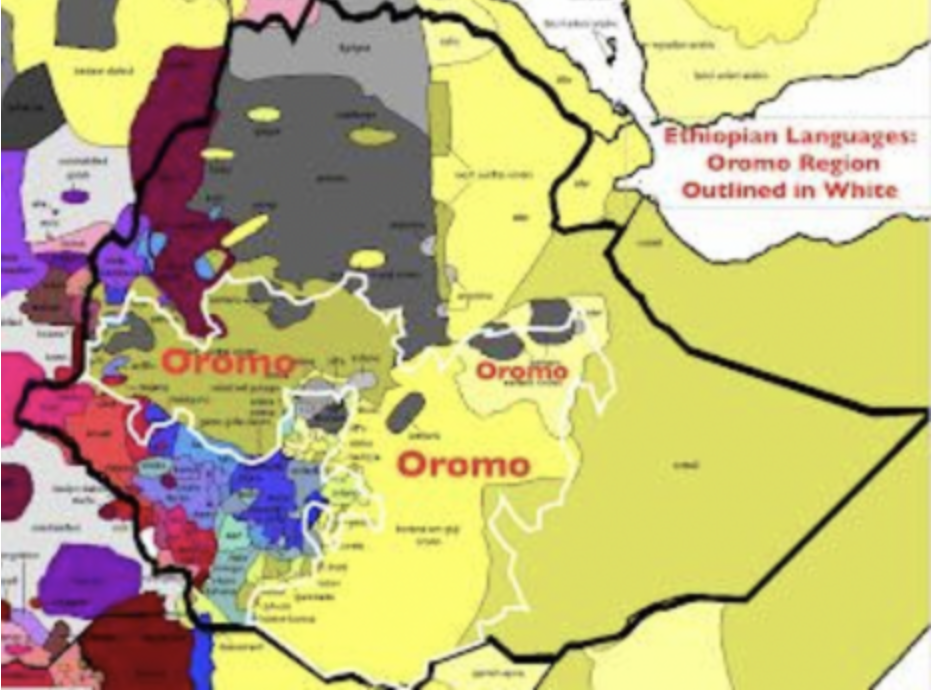

One reason we all underestimated Tigray is that no one outside TPLF circles seems to have admitted to themselves how much of the combat power of both Eritrean and Ethiopian forces came from ethnic Tigrayans. Admitting that would be politically unwise, especially in Ethiopia. Officially, Ethiopia is a federal, multi-ethnic state in which all ethnic groups are equal. But that’s a polite fiction. The Ethiopian state is the product of 19th-c. conquests by the “Habesha,” which is what the Highland Orthodox peoples, Tigrayan and Amhara, call themselves. Ethiopia was created by Habesha armies pushing south and east, absorbing Somali, Afar, Oromo, Sidamo, and dozens of other peoples who became Ethiopian citizens, but had very little share in ruling the country.

Ethiopia ethno-linguistic map: until now, power was in the hands of the two groups in gray

The real struggle for power was always between the two Habesha peoples, Tigrayan and Amhara. Since Menelik II moved the capital southward to Shewa, the Amhara seemed like the stronger of the two groups. Amhara are a much bigger group, for starters. Tigrayans are only about 6% of the population, Amhara about 26%.

But after the Eritrean/Tigrayan insurgents destroyed the Derg in the late 20th c., it was the Tigrayans of the TPLF who really ruled Ethiopia. Their domination was so clear that the TPLF tried to minimize their power, dutifully talking about their multi-ethnic coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). No one was fooled; it was the TPLF who had the power in Ethiopia.

The TPLF leader Meles Zenawi was the ultimate power in the country all through the first two decades of this century. Zenawi knew that the TPLF was so much better organized than the other members of the EPRDF coalition that he and his fellow Tigrayans could let the EPRDF make a show of ethnic equality while keeping Tigrayan control. Henri IV went through the motions of converting to Catholicism in return for the throne with the line “Paris is worth a mass or two,” and Zenawi seems to have decided “Addis and the whole GDP is worth letting those weaker militias from other ethnic groups share the credit.”

Zenawi’s PR campaign worked so well that Ethiopians forgot the hard truth that it was the Tigrayans who had the real combat power.

The Tigrayans’ only rival in terms of military power was the Eritrean army (EDF.) The “Eritrean” label made people forget that the EDF is also dominated by ethnic Tigrayans. Tigrinya-speakers are the majority in Eritrea, not only the dominant but the biggest ethnic group.

That has never stopped Eritrean Tigrayans from killing other Tigrayans. That shouldn’t be a surprise — when have people of the same ethnic group ever fretted about killing each other? — but it does underline what seems like the dominant fact at the moment: The Tigrayans are the most formidable people in the Horn.

Why didn’t Abiy Ahmed and his generals realize that before deciding to invade Tigray in 2020? Well, one thing you discover when you read the Twitter war that’s been blazing since the invasion is that Amhara have a weird double view of Tigrayans, one typical of large groups who have been dominated by smaller groups. Amhara tweeters seem to believe that the Tigrayans are simultaneously all-powerful, conniving, clannish supermen, and parasites who can and should be crushed.

The trouble with this sort of stereotyping is that, if you stress the “weak parasites” pole, you can end up thinking that crushing the hated minority will be a cakewalk. Which brings us to Abiy Ahmed’s choice to go to war in 2020.

The TPLF had been running the country far too long; most Ethiopians seem to agree on that. The hated Tigrayan minority might have overseen a big jump in economic growth, but it just plain rankled having this small group running the country, thinking they’re better than other Ethiopians. Abiy, whose background is mixed Amhara/Oromo, was the choice of Ethiopian voters who wanted the other, bigger ethnic groups to have power commensurate with their numbers. Zenawi, the TPLF leader who’d been pulling the strings, died in 2012, weakening Tigrayan control. Six years later, Abiy Ahmed was elected on an anti-corruption and implicitly anti-Tigrayan platform. If his agenda hinted at violent revenge against the snotty Tigrayans—well, maybe people liked that too. Voters aren’t as humanist as pundits like to think, as the past few years/decades/centuries have shown.

That was the situation at the start of the war: The TPLF was hunkered down in Mekelle and other Tigrayan cities, planning for their response to the inevitable Ethiopian attack. They more or less provoked that invasion when they decided to hold elections in Tigray, even though Abiy had announced that all elections were cancelled because of Covid. Rashid Abdi, a journalist who covers the Horn, warned that war was coming on October 30, 2020.

Since Abdi is close to the TPLF leadership, he probably got his info from them. So they knew Tigray was going to be attacked. They decided to strike first, hitting ENDF bases in every Tigrayan city on November 4, 2020.

TPLF special forces grabbed the local commanders of the ENDF, took any weapons they thought might be useful, and packed ENDF soldiers into trucks for transport to camps far away from the cities. Some ENDF commanders who were ethnic Tigrayans collaborated with the TPLF during the raids and joined the Tigrayan forces.

Two days after these preemptive TPLF attacks, the ENDF answered with air raids, a classic first move by national governments dealing with an insurgent province. The Ethiopian command also unleashed their own ethnic-Amhara militia, usually called Fano (or Fanno — it means something like ‘Ronin’ in Amharic). These were used to terrorize soft targets — Tigrayan civilians in the south, near the border with the Amhara province.

At the time, most news sites took the Fano’s deployment and subsequent massacres and rapes as proof that the fighting in Tigray was just another African atrocity, to be deplored and then ignored. That was totally wrong. For centuries, wars in the Abyssinian Highlands have been highly organized, conventional affairs, not “bush wars.” So the atrocities committed by various forces should be seen as a standard military tactic, a way to use troops with low combat value to create chaos and terror among the enemy population.

Eritrea, pushing into Tigray from the north, soon showed that it had a different policy for terrorizing the Tigrayan towns it conquered. While the ENDF preferred deniable Fano men for its pogroms, Eritrea used its regular troops to commit atrocities. This too made conventional military sense. Eritrea had no interest in winning hearts and minds in Tigray proper, so it didn’t need a deniable irregular force to do the dirty war. Nor did Eritrea have any reason to worry about “international opinion,” since it’s already a pariah state, walled off from the world of NGOs, first-world advisors, IMF plans, and the rest of the standard African-state package.

Ethiopia’s needs are totally different. It’s heavily dependent on Western aid, tight with the NGOs (until lately anyway), and must think long-term about a way to reconcile Tigrayans to its continued rule (assuming it was going to win, of course). So it makes simple cold-blooded sense for Eritrea to let its own forces commit atrocities, while Ethiopia either farmed them out to Fano or tried to hide them.

Ethiopia’s resort to using Fano signaled something else: desperation. Few people realized it back in November 2020, but the ENDF’s reliance on Fano from the very start of the war meant that they knew their army had lost most of its combat power when the Tigrayans defected.

Fano Militia: Amhara Twitter began calling them “the saviors of Ethiopia” in the Summer of 2021, suggesting how badly the war was going for the ENDF proper

There was also, from the beginning, an interesting difference in the way ethnic Tigrayan soldiers behaved when serving with the Eritrean and Ethiopian forces. The EDF was able to order even its ethnic Tigrayan soldiers to carry out massacres against fellow Tigrayans. The ENDF was not. It’s an interesting divergence. Was this because the EDF is more disciplined, or because their Tigrayan soldiers buy into the new Eritrean identity rather than their Tigrayan heritage? Whatever the explanation, it seems clear that the EDF kept its Tigrayan recruits, while the ENDF lost theirs and had to call up an ethnic-Amhara militia as backup.

However, these terror weapons — air strikes and massacres — weren’t going to reconquer Tigray. That would take a big offensive aiming for Mekelle. The expected pincer movement began about a week after the TPLF’s preemptive attacks. The Eritreans sent armor and infantry south into Zalambessa, in northeastern Tigray. Zalambessa is another of those towns which have become metonymic for endless war. I was writing about war in Zalambessa 20 years ago.

The ENDF seemed to be advancing too in the first few weeks of the war. ENDF armored columns rolled into Alamata on the A2 highway, which leads straight north from the Amhara heartland to Mekelle. The ENDF was striking for the heart of Tigray and it didn’t seem like anything could stop them. As far as most pundits could tell, the TPLF was just getting rolled up by the bigger, better-armed ENDF.

We at Radio War Nerd had enough sense to avoid premature predictions of a quick Ethiopian win. We stressed that the TPLF had fought and won a classic Maoist insurgency against terrible odds once before, against the Derg, so it couldn’t be counted out too soon.

Still, even to us, the strategic picture looked pretty grim. The ENDF was rolling toward Mekelle from the south, and the Eritrean army was attacking from the north on a wide front. Even Somalia, which has problems of its own, had loaned thousands of troops to the war against Tigray.

How could the TPLF hold Mekelle against forces like that?

By the end of November 2020, the answer seemed simple: They couldn’t, and they hadn’t. The ENDF moved up the A2 road with only minor fighting and took Mekelle on November 28. The TPLF said it had left the capital and moved into the mountains to wage a guerrilla campaign, but we’ve all heard that kind of claim, “It’s not over!” way too many times. The TPLF’s threats sounded like face-saving rhetoric.

Well, that turned out to be wrong. They meant every word of it. The TPLF’s strategy worked like a training video for Maoist insurgency. It may not work everywhere (thinking back to the sad RCMP recruiters peddling Red Guard badges on Sproul Plaza) but in poor, mostly rural countries with weak central governments, it is extremely effective. Mao doesn’t get much credit—a lotta Bolshevik-love going around and none for Mao—but in my anything-but-humble opinion he will be remembered as the preeminent strategist of the last century. The TPLF had done exactly what their PR claimed they had done: withdrawing from the cities, avoiding battle, and regrouping in the boonies.

The thing about Mao’s strategy, though, is that it’s slow. That makes it very difficult for the CNN/BBC model to cover. Day after day, nothing happens—until it happens. The guerrillas withdraw from the cities, and it’s easy to conclude that they’ve simply fled, headed home, given up. You can refresh your browser fifty times a day and there’s no news, no maps moving, no sign of anything but a total rout.

Looking back now, there were signs that the Ethiopian army’s victory wasn’t as complete as it seemed. For starters, where were the leaders of the TPLF? They should have been the most valuable trophies for a victorious ENDF, but only one of the top leaders, Abay Weldu, was captured.

The most important catch of all, TPLF overall leader Debretsion Gebremichael, had slipped away. There were all kinds of rumors about him: he’d fled to Sudan, or South Sudan, or the mountains, or had been killed.

It wasn’t until early 2021 that there was any reliable news about how the fighting in the Tigrayan countryside was going. And when it came, it was more bad news for the Tigrayan forces. In a conversation with journalist Alex de Waal, a TPLF veteran said that in the first month of the war, the TPLF had decimated the EDF, ENDF, and Fano attackers. Then came the UAE drones.

“And then the Emirates came. The Emirates effectively disarmed Tigray. They started killing tanks, then howitzers, then fuel, then ammunition. Then they started hunting small vehicles, targeting leaders, [indistinct] all over. This created [unclear: risk?] and sort of dislocation, and this is part of the weakness of the preparation. So many people moved out of the cities of Tigray towards the rural other areas following the army, some including their families.”

We know now, though, that the drones were not decisive in the war. Despite them, the TDF won. One of the most interesting military questions coming out of this war will be why drone warfare, which was decisive in Nagorno-Karabakh, was not in Tigray.

Maybe the difference is between the Maoist model of war-fighting and the Soviet one. The Tigrayan forces didn’t commit everything they had to stopping the ENDF as it rolled in at the end of 2020. They pulled back, maybe using a few suicide squads to delay the Ethiopian advance (those would be the tanks and other assets destroyed by drones) but putting their big bet on watching, waiting, and looking for weak points in the occupying force. It’s pretty clear, by 2021, that that’s the way to fight a high-tech occupying force. By this time everybody knows what happened in Iraq and Afghanistan. It’s no secret how to defeat a massive occupation…if you’re willing to pay the price.

And it’s a terrible price. It’s hard to see how terrible the price is until you read a lot of insurgent memoirs. You do not want to live through an insurgency. It’s not romantic, it’s not adventurous, it’s a nightmare. Because another lesson of Iraq and Afghanistan is that recent experiments in counterinsurgency doctrine, the theory that says “We can win the insurgent people over without terrorizing them”—well, even if those were carried out as cleanly as they claimed (and they weren’t)—even then, they do. Not. Work.

The Armenian forces in Artsakh didn’t have the strategic depth to use Maoist strategy, even if they wanted to. In fact, they were using an adapted Soviet model, heavy on armor, artillery, and prepared positions—and were expecting the same kind of war from the Azeris, who trained in the same Soviet school. But the Azeri army, with all the money on earth behind it, plus the discreet backing of every member of the dominant cartel — the US, Israel, NATO, the UAE, and Turkey (“our NATO ally”), brought a new mode of war-fighting, using drones to destroy all that Armenian armor, all that artillery, all those prepared defense points, right off the hilltops.

It might also be that the Artsakh Armenian community, a small population, could not accept the casualties this sort of war creates. The Tigrayan population is more numerous and poorer, with very recent experience of horrific warfare. They may simply have been more willing to pay the terrible price. Or perhaps they simply had no other choice; invading armies with a vengeful ethnic agenda don’t offer civilians the chance to surrender peacefully, and Tigray, unlike Artsakh, did not have Russia right next door to help it negotiate a settlement. It was pretty much fight or die.

The TDF also relied less on prepared positions, making their squads harder to drone. Mao’s strategy relies on mobility and patience. He once claimed that a bandit chief told him “All you need to know about war is circle around, circle around, circle around.” That couldn’t have worked in a tiny theater like Nagorno-Karabakh, but it was perfect for Tigray. Central Tigray looks eerily like Monument Valley where they used to film all those Westerns. Lots of room, lots of hiding places and ambush sites:

John Wayne territory, vs…

…Tigray Defense Force turf

So though the ENDF’s drones probably wiped out the TDF rear guard, they didn’t decide the war. And with TDF moving in the countryside rather than holding a front line, they were harder to find and kill.

Killing was the plan. The ENDF didn’t even bother with trying the new-model COIN. They just killed people. The horrible truth is that that’s how COIN works. That’s what Julius Caesar did in Gaul, and many other commanders before and after him.

The goal is not usually to kill all of the target population. (Though there are plenty of examples of that policy in the record, as recently as Rwanda in 1994.)

More often, the goal is to commit atrocities so lurid that they shock the enemy population into running away. That’s the key: make them run away. When civilian populations have to flee, especially very poor people with lots of children, they will die on their own. And their children will die first. Children die quickly when there’s no food or rest.

This is why those “senseless” slaughters you read about are not senseless at all. They’re traditional, universal practices designed to create horror. Horror makes the enemy civilians run, and running kills them very efficiently. Better yet, the news sites don’t see the connection and attribute their deaths to “famine” or “wartime chaos,” letting you, the occupier, off the hook very nicely.

Rape is a big part of this process. Mass rape breaks the spirit of the enemy fighters, because one of the universal goals of male defenders in every war ever is protecting the women. It’s no accident that there’s a long scene of Scarlett O’Hara being menaced by a leering Union soldier in Gone with the Wind. And it’s no accident she shoots him dead, either—because that was a very pro-Dixie movie, and defeated elites need literary victories, over and over.

IRL, rape victims rarely find themselves on the stairway of a mansion with a pistol conveniently to hand. 999 times out of a thousand, they have nowhere to run when the enemy trucks roar into their towns or villages. They may live after being gang-raped, but their lives have been destroyed, and any children they have will be pariahs. So rape, like massacre, is intentionally horrific, rather than “senseless.” A monstrous sense is still sense, and a far more common form of it than we’d like to think.

Soldiers of the Eritrean Defence Forces seem to have done more than their share of these atrocities. It was the Eritreans who committed the biggest massacre, or at least the biggest one we know about, in Aksum.

The Ethiopian command might have been under some sort of weak directive to take it easy on the horrors (“Remember, we want to make the survivors good patriotic Ethiopians again!”) but the Eritrean command clearly became more brutal as Tigrayan resistance increased. They wanted to bring the nightmare to Tigray, and by all accounts they did a good job of it.

We can’t know for sure exactly which force did which massacre. From the very beginning of the war, Eritrean units went into battle wearing Ethiopian uniforms. The official story in both Ethiopian and Eritrean media on the war for the first few months was that there were no Eritreans fighting in Tigray. It wasn’t until April 2021, five months into the war, that Eritrea admitted it had invaded northern Tigray. And even then, they didn’t exactly admit they DID have troops there; they just said “We are now withdrawing our troops from Tigray.” That’s the sort of fine distinction that foreign-affairs officers love, though its fine-ness is usually lost on the locals who have been getting raped and killed by those un-acknowledged invaders.

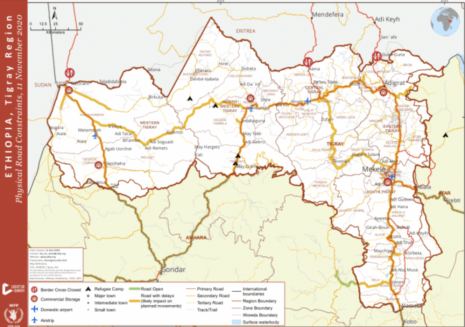

I mentioned that the Tigrayans retreated “to the mountains,” and that was true. But there are a lot of people in the world now, and roads were as big a factor as topography. Ethiopian and Eritrean armor, drones, and aircraft had enough destructive power to control the roads, but a lot of the province is off-road through sheer poverty. So the TDF regrouped away from those roads and cities. This led to the classic guerrilla situation: the occupier controls the cities, the roads, and the daytime, while the guerrillas own the countryside and the nighttime.

Tigray road system, with the key A2 road running straight north through Mekelle

The Ethiopian forces were much more road-bound than the TDF. In fact, destroying the TDF’s armor early in the war might have helped the TDF avoid the temptation of pitched battles along major roads.

Road-bound armies do better on flat land than in rough terrain, so the Ethiopian forces were dominant in the flat plains of western Tigray. To the east, in the highlands where most Tigrayans live, they had a much harder time.

Western Tigray, with its friendly topography, was the front assigned to the Amhara militias. They considered big parts of the area Amhara territory, and when they took control of it, they reacted the way irregular ethnic militias always have: by offering the locals the choice of leaving or dying.

Tigrayan refugees trying to cross the Setit River into Sudan

Well, it seems they didn’t offer the “leaving” option in some cases, but that, unfortunately, is pretty standard ethnic or sectarian militia behavior too. These massacres may have been going on all over western Tigray, but the ones that were reported were concentrated along the Sudan border, in places like Humera and Mai Kadra. That’s a very strategic zone, where Eritrea, Sudan, and Tigray/Ethiopian borders collide. Humera, site of a long series of massacres, is exactly at the point where the three countries meet, and Mai Kadra is a village in the Humera District. So the massacres of Tigrayans there could have been aimed at total extermination rather than the usual “make’em run, then they’ll die” pattern I mentioned above.

It’ll be a long time before anybody knows how many massacres happened in Tigray, but it does seem clear that the pace picked up as TDF ambushes started chipping away at EDF/ENDF/Fano forces. This is another constant of war: When the occupying force starts to take casualties from guerrilla attacks, they react by firing at any civilians in their sights. It’s armies in the process of losing who commit some of the most bloody massacres.

That strategy of reprisal doesn’t work very well against a united population, especially when the occupied people know they will be targeted no matter how docile they are. In fact, that sort of occupier overreaction is a key part of all guerrilla strategies, a way to alienate the people from the occupier. And the ENDF/EDF/Fano forces were more than willing to play the occupier’s bloody role.

The result was nearly unanimous support for the TDF within Tigray. And once an insurgent force has that kind of local support, it can take the offensive. Like good Maoist guerrillas, the TDF must have spent weeks or months watching the occupiers’ outposts, timing their patrols, marking their weak points, and sifting reports to gauge the enemy’s morale, identifying their weak points, their most demoralized garrisons. Once you’ve done that sort of insurgent homework, staging an attack is easy. Well, “easy” isn’t the right word, maybe. Insurgents die at a much higher rate than occupiers in almost all asymmetrical wars. But when the occupiers are as brutal as the Ethiopian/Eritrean/Amhara forces were in Tigray, it’s not hard to find volunteers willing to take the risk of a better death that will make them heroes.

As Yeats said about Irish kids who decided to fight at home rather than on the Western Front in 1916, “they decided to sell their deaths at a better market.”

The TDF’s tactics haven’t changed very much from the ones the TPLF first learned from the Eritreans in the 1980s, as I described them in a previous Radio War Nerd newsletter [#96]:

“…The EPLA had perfected a sophisticated mix of conventional and guerrilla tactics, often sending five columns into an enemy position, with one assigned to kill everyone in the enemy HQ while the others kept the force busy along the perimeter. They used these tactics very effectively against the slow, tired Ethiopian Army, now full of cannon fodder dragged out of Ethiopian villages to replace the slaughtered veterans.”

The biggest weakness of the Ethiopian forces is that they had lost their best soldiers, the Tigrayans. In fact, they were going into battle against them. Some estimates claim that half of the ENDF Northern Command, presumably the ethnic Tigrayans, defected to the TPLF/TDF after Abiy sent the ENDF into Tigray. Most would have taken their weapons and vehicles with them, making the TDF much better-armed than other insurgent groups.

Used tank, needs work

The tactics used to destroy Ethiopian tanks, the ones you see in brief videos from Tigray, probably were very similar to those used in the great Battle of Afabet in 1988. Afabet is deep in Eritrea rather than Tigray, but it has the same kind of terrain as central Tigray, a landscape of sharp rock buttes and narrow canyons with few roads—and the TDF is the descendant of the TPLF, which learned big-battle tactics from the Eritrean EPLF, the force that destroyed the Ethiopian army at Afabet. The EPLF insurgents first forced the Ethiopian forces out of their HQ in Nafka. That forced the Ethiopians to flee south to Afabet. And that ensured an insurgent victory. You can see from this map why an armor-heavy force, fleeing along a classic narrow valley with one road, has little chance against guerrillas with good intel and popular support:

Here’s how that battle developed, as described in my RWN newsletter:

The Ethiopians held for a while, and then the commander of an elite unit, the 29th Mechanized Brigade, decided to break out southward towards Afabet.

Withdrawing with an armor-heavy force, through narrow mountain passes, is a very dangerous move. By this time the Eritreans had quite a significant armored force of their own in action, entirely made up of captured Ethiopian tanks, SP artillery, and APCs. So Eritrean armor, including T-55 MBTs, was trailing the retreating 29th Brigade as they withdrew.

When one of the trucks in the Ethiopian convoy made it to the summit of the pass, an Eritrean T-55 managed to destroy it with a direct hit, and when the T-55’s main cannon hits a truck, it makes quite a mess, especially when the wreckage is right at the top of a narrow mountain pass.

This is the worst thing that can happen to an armor-based force: stuck in a convoy in a narrow mountain valley, with the exit blocked by burning vehicles. All you can do in that situation is get out of the vehicle and try to flee on foot. That’s what the 29th Mechanized Brigade, which had been one of the army’s best units, had to do. Before fleeing they tossed hand grenades into their abandoned vehicles to make sure they couldn’t be used by the enemy. Then they fought their way out towards Afabet, the main Ethiopian base south of Nafka.

When the over-centralized Ethiopian command heard about the disaster they ordered their own air force to bomb the abandoned column, making extra sure those vehicles couldn’t be used by the Eritreans. So at this point you have your own AF bombing a convoy of your best armor. The optics, as they say, were not good: Ethiopian MiG 23s bombing Ethiopian T-55s.

The Ethiopian high command, over-managing from the safety of Addis Ababa, ordered attacks from Keren, the big town to the SW of Afabet, and simultaneous sorties from Afabet toward Keren, to open the road. But that meant sending more armor-heavy convoys along roads that followed the courses of dry riverbeds down long mountain valleys. That’s a defender’s dream landscape. The Italians had discovered that at the Battle of Adwa a century earlier, and the Ethiopian Army, which should’ve known better, was finding it out all over again.

The attacks failed, as the weary Ethiopian troops and mid-rank officers must have known they would. That left the garrison in Afabet totally isolated. And these weren’t the proud Ethiopian troops of the Ogaden War.

They’d been terrorized and mismanaged by their own command for way too long, and the best soldiers had died years ago. Most of them were conscripts rounded up from the streets of the cities, along with any rural kids too slow to avoid the recruiting gangs.

The Eritreans were fast. This was their terrain, they had the enemy demoralized and on the run, and for the first time they could advance by truck and APC. They attacked Afabet on March 19, just two days after beginning the campaign. The town fell fast. Just as in the debacle at the mountain pass, all the Ethiopian commanders could do was blow up what they could and flee south toward Keren.

Most likely the TDF used the Afabet scenario on a smaller scale, dozens or hundreds of times. And the likeliest explanation for at least some of the massacres of Tigrayan civilians is that they were slaughtered in revenge pogroms, after TDF guerrillas destroyed the occupiers’ convoys or outposts. Of course not all the massacres would have happened this way; it’s pretty clear that the Addis Ababa government wanted a mass purge of Tigrayans everywhere in Ethiopia, even in places like Addis Ababa, where there are still plenty of journalists watching. What happened in at least some parts of Tigray, where no journalists were allowed, looks pretty much like straight-up genocide.

It was a genocide that failed, however. As in Syria, the battlefield has trumped the massacre/PR campaign. By July 2021, it was clear that the ENDF was getting run out of Tigray.

On the northern front where the Eritrean forces were invading, things are very different, very grim. Unlike the ENDF, the EDF seems to have held together and fought well. It’s still occupying part of northern Tigray, and by the summer of 2021, Eritrean troops were replacing ENDF/Fano in the flat land of western Tigray, especially the strategic corner around Humera:

“An internal European Union document dated August 20 said Eritrean troops were ‘present in western Tigray, where they have taken up defensive positions with tanks and artillery around Adi Goshu and Humera, and possibly also along the border with Sudan.”

As the war went on, Eritrea got more and more aggressive, even taking over for the fading ENDF on some fronts. As of November 2021, it looks like the TDF hasn’t even been able to dislodge the Eritrean forces from the Tigrayan territory they’ve taken around Aksum. This could be simply a strategic choice by TDF command to attack southward against the ENDF, the weaker enemy.

No matter how you construe it, the control map at this point seems to show that Eritrea is the only faction to gain anything at all from this war.

That’s when you look back at that Ethiopian-Eritrean Pact of 2018, the one that got Abiy his Nobel Peace Prize, and start to wonder if Afwerki lured Abiy, who’s a naïve politician with delusions of grandeur, into a private agreement to attack Tigray simultaneously. Afwerki might even have guessed that the ENDF would be destroyed in Tigray. After all, Afwerki knows the combat power of the Tigrayan forces up close.

Looking cold-bloodedly from Afwerki’s stronghold in the north, it’s a can’t-lose deal: Both Tigray and Addis Ababa would be weakened, while Eritrea would only lose a few thousand soldiers. From Afwerki’s perspective, sending those young men to die in Tigray might be a benefit in itself. Kept at home without jobs (and there are very few jobs in Eritrea these days) they could be dangerous; sent to the front, they will be out of the picture. Better yet, many will not come home at all.

In old-school power-politics terms, Eritrea has done well.

This doesn’t mean that the people of Eritrea have won anything. Afwerki’s clique has won, but his country has gained nothing but a few arid acres and another generation of resentment. Tigray has lost even more. Whenever the war is fought on your terrain, you lose. And Tigray, a very poor place, couldn’t afford to lose anything. After the devastation wrought by the invaders, Tigray will be in poverty and hunger for a long, long time. The TDF victory was heroic, but the price Tigrayans have paid for it is horrific.

Every one of those cars and trucks was a Tigrayan family’s biggest investment

The Ethiopian state may have lost most of all. We may soon be talking about “the former Ethiopia.” It all depends on whether the Tigrayan forces, which have been advancing steadily south on the A2 road, can take Addis Ababa. So far, it doesn’t look as if the ENDF can stop them or even slow them down. In fact, it looks as if the ENDF no longer exists as an effective fighting force.

It’s astonishing, tracking the TDF’s progress since it retook Mekelle at the end of June 2021. As of now (November 16 2021), the control map shows the TDF and its new Oromo allies control the key A2 road as far south as Ataye, only 270 km north of Addis Ababa. But be sure to check the updated map, because by the time you read this the TDF and its allies will almost certainly have moved even closer to Addis.

And from Abiy’s perspective, the TDF advance due south might not even be the most frightening prospect. The scariest threat is that the TDF will push east toward Mille, cutting the crucial A1 road from Djibouti. That’s the route that carries most of landlocked Ethiopia’s imports from the Indian Ocean to the Highlands. If the insurgents cut that road, the Ethiopian government will have to start thinking about negotiating or face collapse.

The biggest new development in the war is, of course, the alliance between the TDF and the Oromo Liberation Army

We said on Radio War Nerd way back when the war started that the Oromo, the biggest ethnic group in Ethiopia, have been getting tired of seeing Highland groups, whether Tigrayan or Amhara, act like they owned the country when the Oromo, more than a third of the total population, have so little power. Oromia is south of the Amhara highlands, so the Amhara, currently the most powerful group in the country, could end up sandwiched between the Tigrayans to their north and the Oromo to the south, just as Tigray seemed to be sandwiched between Eritrea and Amhara.

That nightmare scenario was clear to anyone looking at a map, so it’s not at all clear why Abiy and his handlers couldn’t see it. And now it has come true. The Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) announced an alliance with the TDF in August 2021.

The OLA doesn’t represent all Oromo, of course. In a very standard development, Oromo independence activists have split into two groups along the usual lines: take-it-slow moderates of the OLF and the fight-back-right-now militants of the OLA.

At the moment, the OLA doesn’t have much of a record for armed insurgency. A lot of Ethiopian Twitter-ers make a show of contempt for the combat power of the OLA, a very different attitude than how they talk about the TDF. Basically, the trash-talk from Abiy loyalists is that the OLA is a paper tiger. They speak very differently of the Tigrayans, emphasizing their power and cruelty. But weak insurgent movements can grow strong very quickly when their occupier is distracted elsewhere, as the ENDF is distracted, to put it mildly, in Tigray.

The OLA can also make (probably IS making) a big contribution to the TDF advance even if it doesn’t have a lot of traditional “combat power.” In a war like this, incorporating conventional battles, massacres, and guerrilla raids at once, local support is vital. The OLA may not have the sheer military skill of the TDF, but as the TDF moves into Oromo-populated areas, just having the Oromo guerrillas on your side is a big advantage. They can guide you, keep the locals from fighting you, and warn you about ENDF forces in the area. In that way, the alliance is already paying off for the TDF.

It’s a real possibility, the TDF/OLA taking the capital. Mostly because it doesn’t seem that there’s any force capable of stopping them. The ENDF seems to have dissolved. Abiy called on civilians to muster for the defense of the capital weeks ago (November 2 2021.) That’s a very bad sign for the ENDF. It seems likely that the Ethiopian Army, once a force to be feared, has just plain melted away. And if that happens, the TDF can just roll into Addis the way they rolled into Mekelle a few months ago.

That’s when things could get even nastier. You might be able to keep an alliance like this going as long as you’re fighting a common enemy in the Ethiopian government. What will happen when the war comes to some sort of pause, if not end? What if the TDF makes a deal with Abiy’s people over the heads of its OLA allies? What if the TDF/OLA forces go all the way to Addis and take control of ‘what is now Ethiopia’? It’s a pretty safe bet that their alliance would dissolve in a matter of months, and the country would descend to a multi-ethnic war between provinces, then between towns, as panicked civilians fight for water and food.

Tigray and Oromia aren’t the only Ethiopian provinces with their own ethnic militias. In fact the TDF has made formal alliance with six other groups:

“…The Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front, Agaw Democratic Movement, Benishangul People’s Liberation Movement, Gambella Peoples Liberation Army, Global Kimant People Right and Justice Movement/ Kimant Democratic Party, Sidama National Liberation Front and Somali State Resistance, according to organizers.”

I haven’t even gotten into the next-level nightmare scenarios in which neighboring countries jump into the war to carve out pieces of a dissolved Ethiopia. They’ll regret it eventually–It’s not easy to dial up the precise level of chaos you think you want in a neighboring state–but that doesn’t stop half-bright local Machiavellis from trying, over and over. Ask Erdogan about that.

Sudan, for starters; what’s the plan in Khartoum? How much chaos do they want in Ethiopia?

And what about Turkey? Big player in Somalia, big drone-seller to Addis, and nearly as recklessly aggressive as the US itself.

Then there’s Egypt, which has a much more urgent reason to take up Ethiopia-destabilizing as a hobby, the Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which would reduce the Blue Nile’s flow downstream. Rumors about Egyptian interference have been going around Ethiopian Twitter for a while, and Trump himself lobbed a tactful boulder into the pond:

Which brings us to the nightmare scenario of some kind of American intervention, God forbid. So far the Washington DC interventionist Blob’s attitude to the war in Tigray has had several stages, first looking the other way as the ENDF ravaged Tigray, then miming a more even-handed approach when the TDF started winning, and more recently trying to halt the TDF’s momentum before the Ethiopian state, a big US client/ally, is destroyed. As always, the best thing the Blob could do is stay out of it, but as always, they won’t realize that. They’ll manage to jump in at the wrong time, with the wrong side, somehow or other.

The tectonic plates are still moving in the Horn, and this round of fighting, for all its heroism and overlooked military significance, won’t settle anything. This round of war may peter out soon, though I doubt it. But the war over domination of Ethiopia, or “what is now Ethiopia,” will run hot for decades.

And so far, it looks like every group loses. If any group or neighboring country ends up winning, it will probably one which had sense enough not to jump into the meat-grinder until it’s wearing out. That’s when the big gains are made.

In the meantime, it’s terrible to watch — especially for those like me who admire all the cultures ripping each other apart. These are heroic peoples; they’ve endured so much already; and it’s a safe bet that things will get even worse.

[ad_2]

Source link