[ad_1]

At I Fresh Market in Sunset Park, New York, a working-class neighborhood in Brooklyn, Lily Leong picked up a bunch of spring onions, checked the label, and put them down.

“In the past, one dollar was three,” she said, and then tossed them back into the produce box, where the sign was priced at $1.99. As for beef: “Oh my God,” she exclaimed, “everything is very expensive.”

Leong’s experience more and more coincides with the experiences of food shoppers around the world-whether it’s Brazil, France, Russia or Brooklyn’s Eighth Avenue, where crates and Basket of fresh produce.

The reason for the frustration is simple: global food prices have soared due to severe weather, such as droughts in North and South America and heavy rains in Europe, as well as supply chain problems caused by the relaxation of coronavirus restrictions.

The FAO Food Price Index rose at an astonishing 31% annual growth rate in October. The Food and Beverage Commodity Index of the International Monetary Fund has risen at a similar rate. In fact, after accounting for inflation, global food commodity prices are now higher than their peaks in 2008 and 2011, just before the Arab Spring protests, partly due to soaring food costs.

The Polish Minister of Agriculture is one of those who recently warned of a “food price crisis”. In the worst-case scenario, rising food costs combined with soaring energy prices could endanger the livelihoods of millions of people around the world—just as the world is emerging from the worst pandemic.

Even so, the data shows that the 1970s-style food price crisis that coincided with the famine in some poorer countries has not yet arrived. Although in some countries, especially in emerging countries, food prices are rising at a double-digit rate, in other countries—especially in Europe and parts of Asia—the amount shoppers pay at the checkout counter has actually been declining. .

For example, in the Franprix supermarket near Belleville in Paris, the clerk Ayyoub Ben Belkacem has become accustomed to customers “complaining about food becoming unaffordable.” He explained that although products such as tomatoes and bananas are “really expensive now”, the prices of pasta and pastries have recently fallen.

The main reason consumers’ grocery bills have not risen at the same rate as the index shows is that the latter reflects the wholesale prices paid to producers, which are only a small part of what shoppers actually pay.

For example, of every dollar that American consumers pay for groceries, only 15 cents are spent on food. Marion Jansen, director of the OECD Trade and Agriculture Bureau, said that the rest is used for other costs such as processing, marketing and distribution.

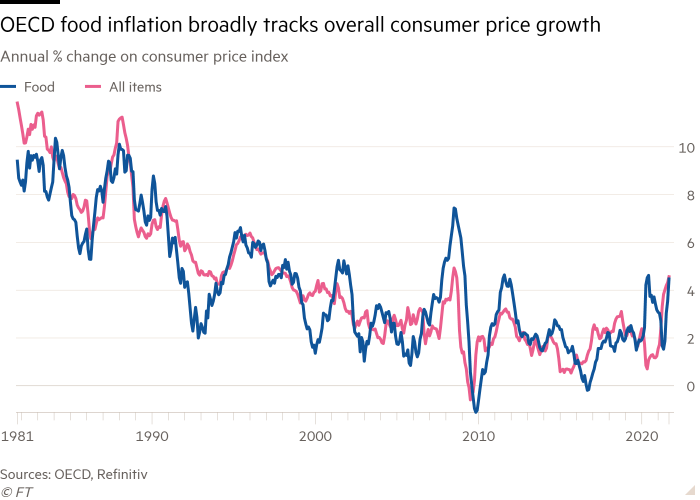

In the 30 major rich countries of the OECD, consumer price food inflation has reached 4.5%. This is three times the amount in the last May. Jansen said that even so, the increase is nowhere near the “dramatic” of wholesale commodity prices so far.

In fact, in advanced economies such as France and Japan, the prices paid by consumers rose by only about 1% in September, while consumer food prices in China, Switzerland, and Belgium actually fell.

This does not help shoppers in other emerging countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Russia or Turkey. There, food price inflation exceeded 10%, exacerbated by the decline in the exchange rate of its currency against the U.S. dollar.

“Because commodities are usually traded and paid in U.S. dollars, this will exacerbate domestic food inflation,” said Christian Bogmans, an economist at the International Monetary Fund.

In Russia, soaring food costs have become a major political issue. Sliding real income Lower the support rate of the ruling United Russia Party to the lowest level in history. In Brazil, the food and beverage consumer price index rose at an annual rate of 12% in September.

Vilma de Souza is just one of many Brazilians. She now wants to know if she can afford the steaks needed for the family’s traditional weekend barbecue.

“I don’t buy red meat anymore, it’s too expensive,” said a maid from Ubatuba, a coastal town in the state of São Paulo. Hearing the conversation, a local butcher interjected: “Many people buy chicken because it is cheaper. It’s hard for everyone.”

Although food prices in developed countries have risen at a lower rate, shoppers still feel pressured, especially those with the tightest budgets. Food prices in the Eurozone have risen by nearly 2%, and in the US they have risen by more than 4%.

Back in Brooklyn, a young couple bought fruit at a small stall on the corner of 8th Ave and 53rd St. They also felt this influence. “Everything is going up,” Nancy said, and her partner Vincent agreed.

The two said they were “okay” and could temporarily cope with price increases. However, if input costs such as energy continue to soar, it may not make sense how long consumers in developed countries can buy the groceries they are accustomed to.

Fiona Boal, head of commodities at Standard & Poor’s Dow Jones Indices, said that ultimately “inflation concerns will spread from energy to other economic sectors, including the food industry.”

[ad_2]

Source link