[ad_1]

A year ago, when emerging markets were struggling to resolve their ability to lock in the economy, wealthy governments avoided difficulties by providing huge financial support programs.

Today, a big question facing the developing world is whether to raise interest rates to curb inflation—another issue that Western central bank officials have been able to postpone so far.

Compared with Western countries, rising prices have posed a threat to the economic stability of emerging markets. One reason is the rapid rise in global food prices. According to a report, global food prices are now close to their highest levels in a decade. Closely Watched United Nations Index.

The price spike reflects what happened before the Arab Spring protests in 2010 and 2011. “The last time it was in the Middle East,” said Hasnain Malik, emerging market strategist at the consulting firm Tellimer. “Who dare to say that the next time it won’t be in Latin America or parts of Asia?”

How to deal with this problem is to classify emerging market central banks as inflation hawks or doves. In Latin America alone, every major economy has exceeded its central bank’s inflation target.

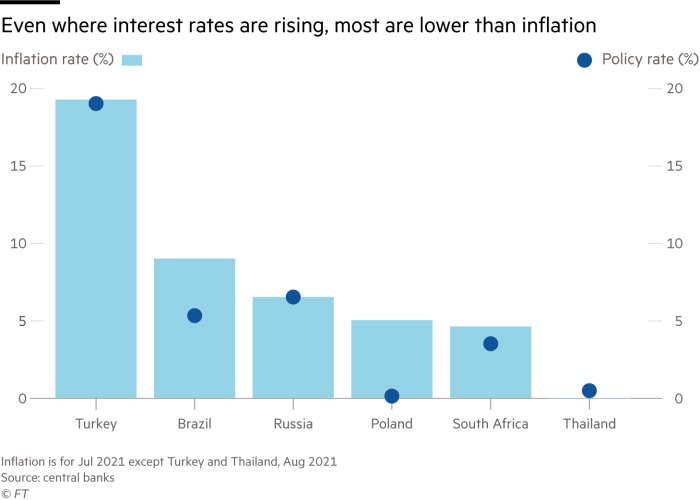

Among the hawks are countries such as Brazil and Russia, which have raised interest rates several times this year to start suppressing rising prices.

In Moscow, inflation is a particularly sensitive issue before the parliamentary elections this month due to soaring food prices.Last week, the central bank announced warn If global inflation is not controlled, a 2008-style financial crisis may occur.

It has raised interest rates by 2.25 percentage points to 6.5%, and it is expected to raise interest rates again on Friday.

The Brazilian Central Bank also tried to keep up with price increases by raising the policy interest rate from a historical low of 2% at four consecutive policy meetings.

However, as the Brazilian real’s exchange rate against its trading partners plummeted, and investors’ reaction to President Jal Bolsonaro’s response to the coronavirus pandemic and his growing Anti-democratic speech.

In contrast, in emerging market pigeons including Turkey and Poland, the government has publicly promoted growth and prices have risen rapidly.

In Poland, the nationalist ruling PiS party is running an expansionary budget, and the inflation rate has reached a ten-year high of 5.4%-which prompted a former central bank governor and government critic to warn that if rising prices are not suppressed , Will face the risk of “disaster”.

However, as this week’s moderate Polish central bank governor Adam Glapinski said, raising borrowing costs would be “very risky”. On Wednesday, the bank maintained its benchmark interest rate at 0.1%.

At the same time, in Turkey, the price is surging 19.25%, because the economy grew by nearly 22% in the second quarter.

Central Bank Governor Sahap Kavcioglu has promised that the central bank’s current 19% policy interest rate will remain above the inflation rate. But he said on Wednesday that the central bank’s policy will be based on core inflation rather than higher overall data, which undercuts this commitment.

Timothy Ash of BlueBay Asset Management said Kavcioglu “will cut back as soon as possible.” Since 2019, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a self-proclaimed “enemy of interest,” fired three central bankers for over-tightening policies.

Analysts say that the government’s lockdown measures to fight the pandemic have played a decisive role in inflation.

Countries that have not sought to shut down their economies are now experiencing faster growth and higher inflation, just like India.

“For those [governments] Absorbed the pain of illness, hospitalization and death caused by Covid, on the other hand they gave the economy a respite,” Malik said. “This means that activity continues and pushes up inflation. “

The opposite is true in countries with stricter blockades, such as South Africa and parts of Asia.

In Thailand, which currently has the strictest blockade restrictions in the world, the inflation rate in August fell by more than half to 0.02%. In South Africa, which was severely blocked last year but was still hit hard by Covid-19, the inflation rate in July fell to the lowest level in three months.

Tatiana Lysenko, chief emerging market economist at Standard & Poor’s Global Ratings, said that in these countries, “there is a deflationary story.”

As for China, which has adopted a zero-Covid approach to the pandemic, producer prices are rising, spurred by increased international demand. However, consumer price inflation has dropped to around 1%, and the central bank is expected to ease monetary policy to keep the recovery on track.

This is a question facing policymakers around the world: which is worse, stagnation or instability. But in emerging markets, if inflation gets out of control, the risk may be higher.

Even among the hawks, only Russia currently has higher interest rates than inflation. If other countries want to bring prices under control, they may have to raise interest rates further.

Additional report by Ayla Jean Yackley in Istanbul

[ad_2]

Source link