[ad_1]

Global Trade Update

Sign up for myFT Daily Digest and be the first to learn about global trade news.

The closure of the world’s third-busiest container port terminal is just the latest sign that sea turbulence may occur next year, posing a threat to global economic growth, as long-term delays and soaring transportation costs may lead to unsatisfied demand and push up consumers. price.

Last week, the outbreak of the coronavirus caused the partial closure of Ningbo-Zhoushan Port, which resulted in the suspension of inbound and outbound container ships, reducing the port’s capacity by one-fifth. Prior to this, another epidemic broke out in China in May, which caused the Shenzhen Yantian Terminal to be closed for three weeks and had a knock-on effect on international shipping.

The continuous increase in shipping prices and the continued bottlenecks in ports around the world have exacerbated a series of problems affecting the supply chain. These include semiconductor tightening and rising raw material prices, as well as a shortage of truck drivers due to retailers stocking up before the shopping season.

Importers and exporters are struggling to recover the costs caused by rising transportation costs. The cost of transporting a 40-foot container from China to the West Coast of the United States has soared to approximately US$15,800-which is ten times the level before the pandemic. According to data provider Freightos, last month.

This disruption began in the second half of last year, when a pandemic hit, carriers suspended flights and demand for goods declined, but then blocked consumers ordered products online at an unprecedented rate.

Efforts by shipping companies to catch up were frustrated by the blockade of the Suez Canal and the closure of the Yantian terminal in March, as well as border restrictions and the absence of port workers.

The indefinite partial closure of Ningbo-Zhoushan is the latest issue that may exacerbate global logistics pressure. Shipping companies have already started to cancel calls at Chinese ports near Shanghai.

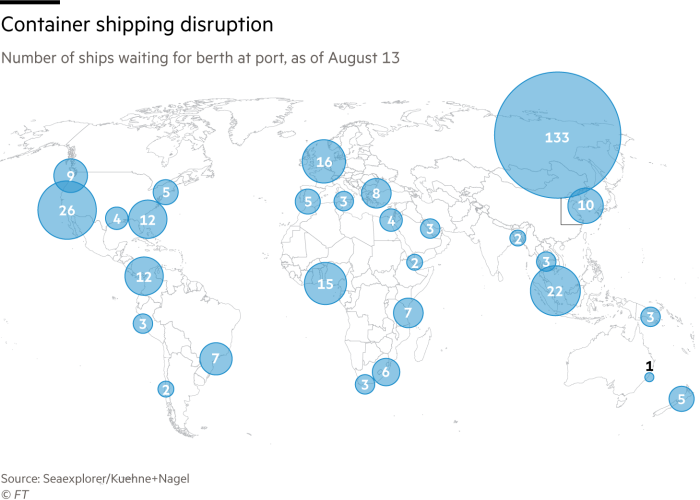

According to reports, about 350 container ships capable of carrying nearly 2.4 million 20-foot boxes are waiting in ports around the world. Ship valueData from Clarksons Platou Securities shows that congestion is getting worse, with idle capacity accounting for 4.6% of the global fleet, up from 3.5% last month.

Lars Mikael Jensen, head of the global ocean network at Maersk, the world’s largest container shipping group, agreed that since the emergence of Covid’s Delta variant, the situation has shown no signs of improvement.

“In general, the situation has not improved,” he said, adding that the maritime transport network “is still very tight-it only takes one small thing and you will go back to one square or one square minus.”

John Glenn, chief economist of the Chartered Purchasing and Supply Association, said that the explosive increase in container freight rates and supply delays will have major consequences.

Although he emphasized that the supply of most commodities is still “sufficient even if it is not very abundant,” the problem is particularly prominent for products that are bulky and low-value, such as foam and colored lights from furniture suppliers.

“Now is the key to supplying supplies to Europe during Christmas,” Glenn said. The forecast shortage of seasonal commodities will push up inflation because “there is no short-term solution and the problem will not disappear soon.”

German airline Hapag-Lloyd estimates that this interruption will not ease until the first quarter of next year. But CEO Rolf Habben Jansen also warned that the date may be delayed due to strong demand.

He said: “Some industries have set record output, a lot of stimulus measures and low inventory levels.”

In addition to the most severely affected industries such as automobiles and textiles, more and more companies report that they have difficulty meeting demand and coping with pressure to increase prices.

In Europe, these effects have been reflected in the weak summer industrial production. “Supply chain disruptions may put pressure on industrial production in the euro zone for a period of time,” said George Barkley, chief UK and euro zone economist at Nomura Securities.

These disruptions have prompted larger manufacturers and retailers to consider strengthening their supply chains by holding more inventory, double purchasing, and even shifting production. But this comes at a price, and for many small companies, this has become a question of survival.

“I think this is the biggest threat to the economy right now. It is just beginning to be affected,” said Philip Edge, CEO of Manchester-based freight forwarder Edge Worldwide Logistics. “Imagine if the price of oil rises from US$20 per barrel to US$200 per barrel, then this is equivalent to what is happening now.”

Although this comparison is inaccurate — shipping sets prices higher in long-term contracts than in the oil market — it illustrates the pressures faced by industries that rely on long-distance transportation.

James Hookham, secretary-general of the Global Shippers Forum, said that the pain is particularly serious for companies in developing countries that supply Western markets.

“The reason for killing these companies is the lag between the higher cost of each voyage and the next opportunity they renegotiate with their customers, which can take 9 to 12 months,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link