[ad_1]

This article is a live version of our Unhedged newsletter.registered Here Send the newsletter directly to your inbox every business day

Welcome back.Today, we jumped into the market and returned to the machine and went to Mid 1980s. Please play Bon Jovi’s “Live by prayer“Play at maximum volume while you are reading this article. Email me [email protected]

United States 2021, Japan 1987

Because I am a pessimist by nature, this newsletter usually talks about downside risks. But for us who are cautious, upside risks can be equally dangerous. For those with conservative positioning, a rebound that melts the face really hurts. And there are reasons to think that we might only have one of them in the next few years.

One way to express this possibility is to say that the US stock market is similar to the Japanese market in 1987.

This is not a perfect analogy, but it provides information. This is a chart from Absolute Strategy Research, showing Japanese and US stock prices and P/E ratios, lagging 35 years:

If you exit the market when the price multiples seem crazy—just like when the P/E ratio reached 35 in January 1987—you can sit there and not invest, and your indiscreet friend becomes very rich.

Ian Harnett of ASR believes that this chart tells the story of Japan’s poor fiscal and monetary policies, which have been too loose for too long:

“If improper monetary and fiscal policies are adopted, the risk lies in [the excess] The first is not CPI inflation, but asset price inflation. .. This is how you suddenly destroy all your mean reversions [stock valuation] Role model. Exit at a price-to-earnings ratio of 35 times because you are three standard deviations from what you saw before, and then doubled again. “

He thinks the current policy may also be inappropriate, he pointed out letter Earlier this week, Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, stated in the Financial Times:

“The large-scale monetary and fiscal stimulus injected by advanced economies is disproportionate to the magnitude of any possible gap between aggregate demand and potential supply… Political pressure to assist in financing budget deficits, unwise central bank commitments will not Premature tightening of policies and the central bank’s extension of mandates to political areas such as climate change pose threats… Slow response to signs of rising inflation.”

Kim refers to the “deafening silence” of central bank officials on broad money growth. In my ears, what is deafening is the silence of ordinary people about high asset prices, which is the analogy with Japan in the 1980s.

But bubbles are complicated things, and we should carefully check whether the Japanese analogy is really useful. Here, I move forward cautiously. I am not an expert in economic history. I hope readers can respond to the following content, if it is not other types, they will definitely make mistakes or simplify.

The roots of the Japanese bubble can usually be traced back to the 1985 Plaza Accord, an agreement between Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany to depress the value of the U.S. dollar. The strength of the U.S. dollar has caused trade imbalances and is stifling ( Including other things) American auto industry. The subsequent appreciation of the yen caused Japan’s export-oriented economy to fall into recession.

However, after exiting the recession in early 1987, Japan began to roar: strong real GDP growth driven by a large amount of fixed investment, currency still strong but stable, loose monetary policy and growing money supply, and consumer price inflation. It’s high on the side but it doesn’t look dangerous. Everything is just right.

The Bank of Japan soon became uneasy about inflation. But people are very concerned about keeping interest rates low to ensure that the yen will not appreciate again. The stock market crash in 1987 frightened central bankers around the world and had to keep interest rates at lower levels for longer. Despite its strong economy, Japan has done the same. The central bank did not raise interest rates until 1989, when asset prices reached a heroic peak.

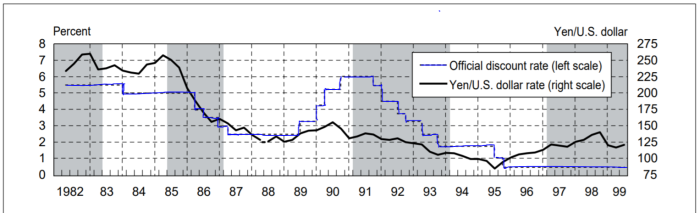

This is from a chart Excellent paper Regarding the bubble of the Bank of Japan economists Kunio Okinawa, Masaaki Shirakawa and Shigeru Shirazuka, the yen’s interest rate policy is stronger:

The loose monetary policy is obviously not caused by the bubble itself. Radical bankers, deregulation, excitement and other factors all played a role. But the Bank of Japan economists concluded that, despite official concerns about inflation, keeping interest rates low until the end of 1989 is the key:

“Considering the relationship between the emergence of bubbles and monetary policy, the most important point is that in the context of economic expansion, due to the maintenance of low interest rates, after a certain point in time, expectations that the then low interest rates will continue indefinitely surged, resulting in Strengthen the effect [other] The mechanism of asset price increases. “

This picture (and the author’s comments on the public and political pressures of low interest rates) fits the current situation in the United States, where long-term inflation expectations in the United States are still suppressed, helping to justify high asset prices.

For Harnett, the key is that Japan uses loose monetary policy to push down the yen, which is impossible for it to do, and trouble ensued. This time in the United States, monetary policy was used to make the U.S. economy more equitable. It is the wrong tool again. The economic shock helps justify these two policies. In Japan in the 1980s, the shock was the Plaza Accord and the 1987 crash. In the United States today, it is a pandemic.

Albert Edwards, strategist at Société Générale, summed up my point very well:

“Just as a strong currency allowed Japan to implement a changed monetary policy, the shock of the pandemic also allowed policymakers to cross the Rubicon for monetary and fiscal cooperation. The pandemic allows regime change, just like the Plaza Accord.”

Pelham Smithers, who leads a London research institute that has long focused on Japan, added an important point. In the late 1980s, it was easier to tolerate high asset prices because, just like in the United States today, many companies have achieved truly outstanding results:

“The summer of 1988 was when things like the Japanese Iron and Steel Company broke out. This is not a pure commodity boom, but a company that has done very well in the real world. They raised prices, increased quantities, and did not face costs. The problem of rising… The companies that have suddenly made a lot of money are rising. The economy has recovered and the yen has weakened. These are fixed-cost businesses. This is a triple blow.”

One dissimilarity is the background of the bond market. In Japan in the 1980s, the yield of long-term bonds was higher than that of stocks (that is, higher than the price-to-earnings ratio of stocks). This is a chart from Okina, Shirakawa, and Shiratsuka that shows what they call the yield spread, or the yield subtracted from the long-term bond rate:

The spread in the U.S. is even lower than in Japan in 1987. In fact, it is negative. The yield is lower, but higher than long-term Treasury bonds. From a bullish perspective, this may indicate that the US stock market has gone further than the Japanese stock market.

We may indeed have to prepare for the possibility of the meltdown of Japanese-style asset prices. This does not seem to be a central forecast, but it is not impossible.

A good book

My colleagues Harriet Agnew and Laurence Fletcher sheet Last week talked about the legacy of hedge fund manager Julian Robertson, who proved to be particularly good at spotting talented analysts, many of whom later established their own funds.

How can I become an excellent money manager? Most people think it is the brain, which is really necessary. But many smart people are bad fund managers. A concept that keeps appearing in Robertson’s articles is competitiveness, which I think is actually rarer than high IQ. Everyone likes victory, but a strong hatred of failure is rare and difficult to maintain.

A few years ago, I had a conversation with an executive from a famous family office about the choice of manager. He said that once the head of the hedge fund has a strong interest in charity, it is time to divest. This shows that the competitive advantage is declining. I think what he said makes sense.

[ad_2]

Source link